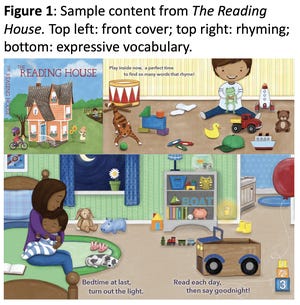

Inside "The Reading House" young children will find a colorful page showing a room with lots of toys strewn about. There is a truck, a bear and a duck.

At a time not too long from now, your child's pediatrician might point to the toy truck on the page and ask your 3-year-old, "What else on these pages rhymes with truck?" The doctor will also ask the child to show her the cover of the book, point to alphabet letters, identify where there are words on the pages.

"The Reading House" is both a children's book and a new tool to help pediatricians identify literacy challenges that preschool-age children may have. It's an assessment that takes only about five minutes and could help parents and early childhood educators change your child's life. The book is already available to pediatricians at low cost. (It is not available for families.)

Dr. John Hutton at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center and his team developed the tool. It fills a gap in pediatric care, he said.

“While developmental screening is a mainstay of pediatric practice, there is no established standard to assess reading readiness and identify children at-risk early,” Hutton said. Often, that kind of literacy assessment is left to teachers. And that means it happens after the child is enrolled in school.

Hutton, director of the Reading and Literacy Discovery Center at Cincinnati Children's, is the founder of Blue Manatee Press, the publisher/distributor of "The Reading House", but he receives no salary or other compensation for this role. The book means that help with reading skills can come sooner for young children, he said.

"The Reading House" helps the screener measure core skills preschool kids typically develop. Among them:

- Vocabulary.

- Rhyming.

- Alliteration.

- Parts of a book.

It gauges performance levels for ages 3-4 and 4-5, according to Cincinnati Children's.

The 70 kids who took part in clinical research with "The Reading House" had fun doing it, Hutton said.

"They don't even realize they're being screened. It's very engaging for the child."

The book is designed so that, once the child's scores are figured, a doctor or teacher can give the book to the child's parent or guardian; the parents can take it home and read it and use it to help the child practice literacy skills. Pediatricians can use their evaluations to talk to families about what else they can do to help prepare their child for reading. The answers might include enrolling the child in preschool, practicing at home, getting a library card or following up with pediatricians periodically.

For the kids, the work (and fun) begins a year or two before they go to kindergarten, which provides time to grow in literacy skills.

Tiana Henry, a Cincinnati Children's community engagement specialist who oversees the medical center's Imagination Library and Reach Out and Read programs, said her daughter enjoyed the book. Henry's daughter read "The Reading House" as part of an early screening process but wasn't in the actual study.

“We are always trying to motivate parents to read to their child as early as possible so their child is prepared for when kindergarten starts,” Henry said. “ 'The Reading House' is not only a fun book for the child, but it also shows parents their child’s areas of strengths and weaknesses, so they can work on those areas while at home.”

Hutton and his team worked with 70 healthy children of varying socioeconomic backgrounds for their study.

In addition to using "The Reading House," the researchers did scans of the kids' brains.

They found that children who had a thinner cortex on the left side of the brain were likely to have lower scores on "The Reading House" assessment. Those with a thicker cortex on the left side had higher scores. Hutton said a thicker cortex, particularly in left-sided areas that support language and reading, has been associated with higher skills that are predictive of reading outcomes.

“By screening early during pediatric clinic visits, especially in practices serving disadvantaged families, we can hopefully target effective interventions that help children better prepare for kindergarten and improve reading outcomes — literally ‘shaping their brains to read.’"

Interventions might include things such as nurturing literacy skills at home, enrollment in preschool, even getting a library card.

Hutton recommends the assessment for kids around age 3, in part because well-check visits for children that age allow for a little more time with a pediatrician because the kids don't get shots at 3.

Dr. Thomas DeWitt, co-author of the study and attending physician in Cincinnati Children's Division of General and Community Pediatrics, said the book will boost life outcomes for children. "Timely identification (of reading challenges) and intervention ultimately means that more children will have a more positive and successful early school experience, which can set the foundation for ongoing school and life success."

Source link