During Tony Dungy's first interview with the Tampa Bay Buccaneers in 1996, he was asked why he thought he had interviewed for so many NFL head coaching jobs and never gotten one.

Dungy, then 40, was exasperated. In the previous decade, he had interviewed just four times. And during two of those interviews, he had been told by team brass that their ideal head coaching candidate had a completely different skillset than his own — offensive expertise, for example, or previous head coaching experience.

"I had four, and two of them for sure I wasn’t going to get, because I wasn’t what they were looking for," Dungy recalled.

Now an analyst with NBC Sports, he brings up his early interviews not because he holds any ill will toward the teams or executives involved, but because the experience illustrates a frustrating catch-22 that is still present in the NFL coaching world — especially for coaches of color.

"When you interview minority candidates, if you really don’t have an interest in hiring them, then it becomes a stain on (their) resume," Dungy explained. "You’ve interviewed 10 times and didn’t get selected, so something must be wrong."

Follow every game: Latest NFL Scores and Schedules

With this year's NFL coaching carousel now in full swing, USA TODAY Sports set out to examine this issue and others by compiling data on head coaching hires in the two decades since the 2003 implementation of the Rooney Rule, which requires NFL teams to interview minority candidates for top positions. USA TODAY Sports also tracked head-coaching interviews over the same time period, using contemporaneous news reports and team announcements.

The data shows that, from 2003 to 2022, interview opportunities for coaches of color were concentrated among a relatively small group of candidates — familiar faces who were interviewed over and over again for head-coaching roles and, in a majority of cases, not hired.

USA TODAY Sports found that a group of just four Black coaches — Eric Bieniemy, Todd Bowles, Jim Caldwell and Leslie Frazier — accounted for nearly 25% of the publicly-reported interview opportunities given to non-white coaches since the implementation of the Rooney Rule.

Bieniemy, the Kansas City Chiefs' offensive coordinator, has interviewed for at least 15 jobs and not been hired as a head coach.

"Obviously, the Rooney Rule isn’t working," said Michael Locksley, the president and founder of the National Coalition of Minority Football Coaches and head coach at the University of Maryland. "It came from a good place, but obviously because of the numbers, it hasn’t created the opportunities that we all thought it would create.

"... You see the same guys being recycled, the same guys interviewing. It’s not that they’re not qualified. Some of them are just being interviewed to basically fulfill a requirement. And we’re not for that."

NFL representatives have said they are taking numerous steps to foster diverse hiring practices across the organization. Over the past three years, the league has expanded the Rooney Rule to require two minority candidates interview for head-coaching jobs, and broadened it to apply to coordinator and quarterback coach positions.

Thanks at least in part to those efforts, USA TODAY Sports found non-white coaches have received a significantly larger share of interview opportunities in recent years — including about 40% of all head coach interviews from 2019 to 2022.

Those additional interviews, however, have not led to a noticeable uptick in hires. Only six of the 29 vacancies during that four-year period (~21%) went to non-white coaches.

"That was one of the anticipated outcomes that I think we all believed when the Rooney Rule was put in place — that more opportunities to interview would lead to more job hirings of minorities," said Rod Graves, executive director of the Fritz Pollard Alliance. "And that hasn’t necessarily been the case."

OPINION:Don't overthink this, Wilks deserves the Panthers job

IN DEPTH REPORTING: Read more of USA TODAY's NFL Coaches Project

'DIDN'T LOOK THE PART':Reasons why Black coaches don't get NFL head coaching jobs

'No rhyme or reason for it'

According to USA TODAY Sports research, no coach has interviewed more frequently over the past two decades than Bowles, the current head coach of the Tampa Bay Buccaneers. The 59-year-old, who is Black, has been up for at least 19 head coaching jobs over eight hiring cycles and been hired twice, most recently last year as the internal successor to Bruce Arians.

Five other Black coaches have interviewed for 10 jobs or more since 2003. Two have yet to be hired: Bieniemy and Pittsburgh Steelers defensive coordinator Teryl Austin (10). Spokespeople for their respective teams declined to make them available for interviews, and their agents did not respond to messages seeking comment.

"You can’t say for sure (if race was a factor)," Austin told The Associated Press in 2021, of why he has yet to be hired. "Maybe I’m not what the owners see when they look in the mirror and they see leadership positions."

Josh McDaniels (16 interviews) and Adam Gase (12 interviews) have been among the most frequently interviewed white coaches. Each has been hired twice.

Among the other findings in USA TODAY Sports' data:

► From 2003 to 2022, a total of 57 coaches of color interviewed for at least one NFL head coaching job, compared to 159 white coaches. That's about three white candidates for every candidate of color.

► The coaches of color in that candidate pool, however, received more interviews on average (4.5 interviews per coach) than their white counterparts (3.2).

► Coaches of color received about 33% of the 769 publicly-reported interviews for head coach positions from 2003 to 2022. They were hired to fill 19.5% of those vacancies.

► Of the nine coaches who have interviewed for the most jobs since 2003 without being hired as a head coach, seven of them are Black. (Darrell Bevell and Russ Grimm are the others.)

USA TODAY Sports' data does not include clandestine interviews, nor reflect multiple interviews conducted with the same team during the same coaching search — i.e., second-round and finalist interviews.

It also excludes three hires made as part of internal succession plans, and a fourth — the Chiefs' hiring of Todd Haley in 2009 — for which no public information is available.

"Watching this thing unfold for 35 years, it’s better — the league is much better. But the hiring process is always a mystery," former NFL coach and ESPN analyst Herm Edwards said.

"It’s not anybody’s fault. I’m not blaming any coach who got hired over another coach. But there’s no rhyme or reason for it, with how people do things."

Hurting your chances by interviewing too much

Dungy got his first interview for a head-coaching job with the Philadelphia Eagles in 1986. He was just 30 years old. "I didn't know what I was doing," he said.

Over the next few years, he was frequently mentioned as one of the premier head-coaching candidates in the NFL — a safe bet to become one of the first Black coaches to get a top job. But in nine years, he only received three more interviews, two of which left him convinced he never had a realistic shot in the first place.

In 1988, at the end of his interview with Green Bay Packers executive Tom Braatz, Dungy said he asked Braatz to describe his ideal candidate for the team's head-coaching vacancy. Braatz told him it would be an offensive-minded coach who had previous head-coaching experience. Dungy was neither.

Then, in 1994, Dungy said he wrapped up an interview with new Jacksonville Jaguars owner Wayne Weaver by asking the same question. This time, Dungy was told the Jaguars wanted a head coach who could also be the general manager. He had no interest or experience in holding both roles.

"You're a little frustrated. You think, 'Gosh, I didn’t really have a chance at this,'" Dungy said. "Can you really blow the owner away and get the job, or is it just a quick perfunctory thing so I can say I filled out the requirement of the rule?"

Dungy said his fourth interview of that stretch, which was again with the Eagles, illustrates the complexity of that question. When owner Jeffrey Lurie described his ideal candidate, Dungy thought he sounded like a perfect fit. He said he called his wife, convinced he would ultimately get the job. Instead, Lurie diverged from his plan and hired Ray Rhodes, who is also Black.

"I don’t think Ray Rhodes was necessarily what Jeff Lurie was looking for," Dungy said. "Ray kind of blew Jeff away."

Arizona State athletic director Ray Anderson, who was Dungy's agent at the time, said he doesn't remember the specifics of those early interviews. But he knows there were plenty of teams at the time who interviewed Black coaches just to check a box — "(more) than will ever be known publicly," he said.

As an agent representing Black coaches, Anderson said he often cautioned his clients to be strategic about which — and how many — interview offers to accept, even for head-coaching roles. Pass on a legitimate opportunity and it might mean losing out on a dream job, but take too many illegitimate ones and it could hurt you.

"If you’re not hired, then you run the risk of one of the 32 owners saying, 'I don’t want to hire a coach who, very frankly, was rejected by three or four other teams already,' " said Anderson, who later served on the working committee that helped develop the Rooney Rule during his time as an executive with the Atlanta Falcons.

"That’s the real dilemma, when you have so few opportunities."

No blueprint for hiring a head coach

For Dungy, this issue gets at the heart of the Rooney Rule — and the late Dan Rooney's intentions when helping to craft it.

The assumption was that NFL owners, like Rooney, would have a blueprint or set of qualifications they were looking for in a head coach when embarking on a search. If a rule required them to interview a coach of color, the idea went, they would naturally interview a coach who fit that blueprint — and maybe it would lead to them getting hired.

In reality, Dungy said, many owners have no idea what sort of tangible characteristics they want in a head coach.

Others have a clear blueprint, then turn around and interview coaches who don't fit it.

The Hall of Fame coach mentioned a conversation he had with one executive during the 2021 hiring cycle, who said his team's owner was set on hiring a young coach with offensive expertise who could help develop their quarterback. Dungy later saw the team interviewed Bowles, a veteran coach who specializes in defense.

N. Jeremi Duru, the author of "Advancing the Ball: Race, Reformation, and the Quest for Equal Coaching Opportunity in the NFL," said the small pool of frequently-interviewed minority coaches reflects a broader theme — that owners want to feel comfortable around the men they interview and hire.

"Generally speaking (among) club owners — an almost racially homogenous group — there tends to be less comfort with candidates of color. And among candidates of color, I think there’s often less comfort with new candidates," said Duru, a law professor at American University.

"I think there may be comfort around some candidates and, as a consequence, they get recycled for multiple interviews. Other candidates have a harder time getting them."

Graves said he generally views an uptick in minority interviews, even among a small group, as a step in the right direction because it means they are getting more exposure.

But he acknowledged it can become problematic in cases like Bieniemy's, where a coach is interviewed over and over again without getting a job — raising questions about preparedness, or creating a stigma that the coach doesn't interview well.

"How many white candidates have been in the same position, where we’ve seen them take six, seven interviews or more and never have gotten a job?" Graves asked. "And are they treated differently, in terms of their perception about their preparedness and ability to coach at a higher level?"

Trying to eliminate so-called sham interviews

In a wide-ranging conversation with USA TODAY Sports in September, NFL officials pointed to a number of policies they have implemented in recent years in an effort to bolster hiring practices in the league.

In addition to expanding the Rooney Rule, the league now requires inclusive hiring training for team personnel who are involved in the interview and hiring processes. It's created networking events and an "accelerator" program to help non-white coaches get face time with team owners. And every year, its football operations team compiles a "ready list," with data and information on top minority coaching candidates.

NFL executive vice president and chief administrative officer Dasha Smith also said the league carefully monitors the head coach interview process, doing what it can to identify and eliminate so-called sham interviews. She acknowledged, however, it is often "very difficult to know" which ones are illegitimate.

"We try to put everything in place so we can look at some objective metrics to try to ensure that it’s not perfunctory, if you will," Smith said in September. "So that is: Who’s in the room? How long are the interviews? Are they in-person, are they (via) Zoom? ... And then we also reach out to the candidates who’ve been part of the process and ask them how they felt about the interview."

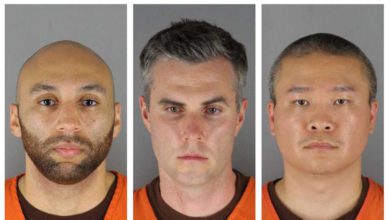

Sham interviews are at the crux of the discrimination lawsuit that a trio of Black coaches — Brian Flores, Ray Horton and Steve Wilks — filed against the NFL and some of its teams last year.

Flores alleged in the lawsuit that the New York Giants had already decided to hire Brian Daboll when they interviewed him for their head-coaching vacancy last year. The Giants denied the claim, saying Flores "was in the conversation to be our head coach until the eleventh hour" but they felt Daboll was the better fit.

Flores has interviewed for at least nine jobs over three hiring cycles, according to USA TODAY Sports research, and he's been hired once — as head coach of the Miami Dolphins in 2019. The team fired him after 2021, and he spent this season with the Steelers. It is unclear if he will receive consideration for open head-coaching jobs during the current hiring cycle.

Dungy said his hope, this year and beyond, is not just that well-known coaches like Flores will get more legitimate interviews and head-coaching opportunities. It's also that young Black assistants, who have never interviewed for a head job, will be included in the candidate pool and given a chance to wow owners.

As a comparison, Dungy mentioned Zac Taylor, a white coach who was a relative unknown before the Cincinnati Bengals hired him in 2019.

"There’s some Black Zac Taylors out there, but they’re not going to get those opportunities — or they haven’t," he said.

"How do you get the young, up-and-coming, unknown Black assistants interviews? That to me is where we can make progress."

Contributing: Jim Sergent

Contact Tom Schad at [email protected] or on Twitter @Tom_Schad.