The accelerating pace of inflation is one of the main economic trends of 2021.

The Consumer Price Index or CPI, the government's main inflation gauge, has ran around a 5% annual pace for the past several months, well above last year's 1.4% rate and the 50-year average of about 3.9%.

Higher rates of inflation have the potential to erode the value of investment portfolios, reviving memories of the 1970s, when large U.S. stocks took it on the chin.

Various investment hedges can help blunt the damage, but the current inflationary trend might not last all that long — and you might already have sufficient protection. Before making any drastic moves into inflationary hedges, consider these issues:

Which assets hedge against inflation?

Various assets can help protect against inflationary spikes. TIPS, or Treasury Inflation Protected Securities, are one obvious example on the bond side. Gold and other tangible assets including real estate also have reputations as inflation hedges. Cryptocurrencies, too, might fit that role.

But during a Sept. 23 webinar on inflation protection hosted by investment researcher Morningstar, the panelists found common ground in a less-obvious area: The stock market.

"You're buying shares in real companies that make real goods and services," the prices of which tend to go up over time in an inflationary environment, said Catherine LeGraw, an asset-allocation specialist at investment firm GMO

Specifically, the shares of natural resource, commodity and real estate companies can fare well during inflationary periods. But other corporations can too, assuming they can pass along price increases to consumers.

In the Morningstar discussion, gold received relatively little attention, though Nic Johnson, a commodities portfolio manager at PIMCO, described the metal as an asset that you can expect to "keep pace with inflation over very long periods."

The panelists spent little time on bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies, noting that they lack any fundamental value. If you invest in cryptocurrencies, LeGraw said, you had better hope that "the next guy will like them better than you do."

Do you need more protection?

Before making any adjustments, it's worthwhile to take inventory of what you own in your investment portfolio. Oil and other energy stocks, mining enterprises, real estate companies and other traditional inflation stalwarts already are included in most broadly diversified mutual funds and exchange traded funds, though perhaps not in the weightings that you would like.

Energy stocks, for example, make up less than 3% of the broad Standard & Poor's 500 index. So too for materials companies and those engaged in real estate. Contrast that with, say, nearly 28% of the index's assets held in information technology stocks, 13% in health care and nearly 12% in consumer-discretionary companies.

For more punch, you might consider adding a bit more to inflation-protected assets such as natural resources or commodity companies, but be wary of overdoing it. As a general rule, allocating 10% or 20% specifically in these areas to an already broadly diversified portfolio likely would suffice, Johnson said.

Also consider the inflation protection offered by other assets you might have, such as a house or rental properties. And if you're collecting Social Security retirement benefits, keep in mind that you can look forward to cost of living adjustments, making Social Security a decent inflation hedge. The Social Security Administration next month will announce the COLA for 2022.

Where is inflation heading?

Predicting the future direction of inflation isn't easy. Despite occasionally alarming headlines, It's possible that we have seen some of the highest numbers in this cycle already. Several long-term deflationary forces remain in place, from global trade and relatively inexpensive imports to the technological revolution, which continues to moderate costs for computing hardware and other goods and services.

America's aging population also could contribute to disinflation, as older people tend not to spend as much on new homes, furnishings, vehicles, entertainment and so on (though more in other areas, especially health care).

The three Morningstar panelists were asked when we are likely to see CPI numbers drop and stay below 4% on an annual basis. Evan Rudy, a portfolio manager at investment firm DWS, said he expects that will occur in the second half of 2022, while Johnson and LeGraw anticipate it happening earlier.

The reopening of the economy from the COVID-19 pandemic has boosted inflation as consumers started buying things they had put off, from vehicles to air travel, and as more people re-entered the work force and were hired.

Supply chains continue to be stretched and that could continue well into next year. Prices for some items already are rising at double-digit rates, and retailers and others are warning of shortages for the holiday-shopping season.

Still, many of these pressures aren't likely to be permanent. Johnson drew a parallel between recent inflationary increases and the start of a marathon. All the runners initially congregate in a small pen behind the starting line, he noted, but as the race unfolds, that congestion eases as runners spread out and find their own paces.

Clues from the past and future

Past periods of high inflation weren't all that common, and unique catalysts tended to spark each such incidence. Back in the 1970s, for example, the OPEC oil embargo pushed up energy and transportation costs, and wages were escalating at a brisk pace. There's no such oil embargo currently, and a relative lack of collective bargaining and union strikes these days suggest that wage inflation isn't likely to become rampant, LeGraw said.

"Do workers collectively have enough power to cause broad wage increases?" she asked. "Right now, workers lack that power."

Bond investors could get hammered if inflation and inflationary expectations continue to rise and if interest rates creep higher, as seems plausible. Bond prices fall and yields tend to rise under such conditions. Yet prices are still high and yields remain near decades-low levels on Treasury securities and many other bonds, LeGraw noted, suggesting that investors don't see these as long-term threats.

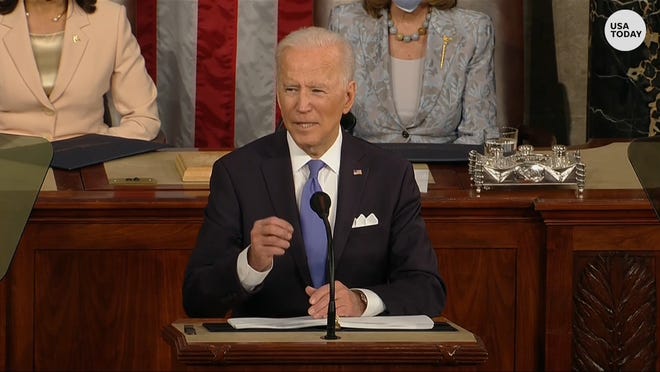

Federal policies also play a role. As an example, the push toward green energy and more electric-vehicle charging stations, as proposed under President Biden's Build Back Better plan, could spark more inflation initially if those initiatives are enacted and construction projects get carried out, Johnson said. But the push to renewable energy could be disinflationary in the long run, he added, if it means cheaper energy eventually.

Reach the reporter at [email protected].

Support local journalism. Subscribe to azcentral.com today.

Source link