Angela Leisure sometimes catches herself talking to her grandson the way grandmothers do when making a point.

She raises her voice and points her finger. She speaks in a tone and cadence that turns what had been a conversation into a lecture, as if every word should be remembered, as if someone’s life might one day depend on it.

Often, those conversations with her grandson, Tywon, are about what happens if he ever encounters police officers while driving.

Make sure your taillights work, Leisure will tell him. Make sure your seatbelt is on. Make sure your music isn’t too loud. If they pull you over, turn on your phone’s video camera. Record everything.

“We want you to come home,” Leisure will say. “Your last name is Thomas. Remember that.”

She never has to explain why that name matters. At 20, Tywon now is a year older than his father was when a Cincinnati police officer shot him to death in an Over-the-Rhine alley on April 7, 2001. Thomas, who was unarmed, was wanted for a series of minor traffic violations when he ran from police that night.

The shooting ignited days of civil unrest, prompted a federal civil rights investigation and led to reforms that changed the way the city’s police do business.

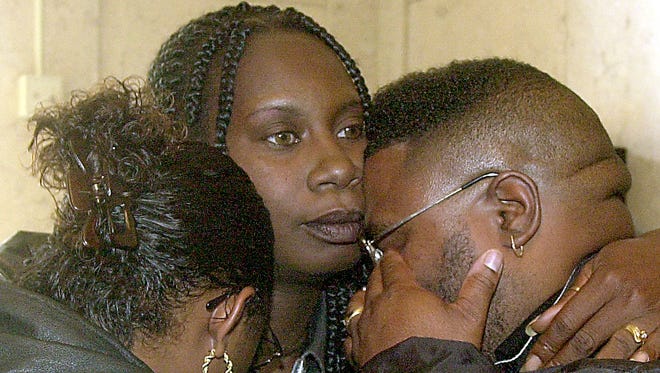

But for Leisure, there was only grief and fear and anger. While the rest of Cincinnati turned her son into a symbol or a rallying cry, a martyr or a criminal, Leisure and her family struggled with the real, day-to-day consequences of his death.

She had lost a son. Her children had lost a brother. Tywon, three months old at the time, had lost a father.

And for the next two decades, all of them would cope with that loss while carrying the weight of Timothy Thomas’s name.

“Sometimes, I look at his son and I see him,” Leisure told The Enquirer in a recent interview. “It’s like looking at a young Tim.”

Everyone thinks they know her son

Her son’s name and face were everywhere for months after his death. A photo of him, smiling and wearing a tuxedo, a red carnation pinned to his lapel, showed up on posters, T-shirts and the evening news.

Once a private memory, something for the family scrapbook, the photo now belonged to everyone. Sometimes, it seemed to Leisure, so did her son.

A few months after he died, Leisure started taking a computer science class at Cincinnati State that she and Timothy had signed up for together. One day, she said, the conversation in class turned to current events.

There she sat, in the back of the room, listening to strangers talk about her son and the police, about what happened that night, about what should happen next. It was surreal.

Leisure, still angry and grieving, didn’t say a word. She was afraid about how that might go.

“This was so raw for me,” she said.

The instructor, though, talked a bit about the need for police and the people they serve to see each other as human beings, not as enemies or as criminals. He said everyone needed to be accountable for their actions, including the police.

Weeks later, before the final class, the instructor pulled Leisure aside. He told her he was a police officer.

She was shocked, since he’d never told anyone in class, but she thanked him for steering the earlier conversation to a quick and constructive conclusion.

“I thanked him for being one of the good ones,” she said.

'I was so tired of hurting'

A year or two later, Leisure said, she was driving on Interstate 75 through Evendale at night when a police cruiser pulled up behind her, lights blazing.

She was speeding, she said, no doubt about that. But the fear that rushed over her had nothing to do with a potential ticket.

Leisure knew Stephen Roach, the police officer who had shot her son, was now working in Evendale. He’d been acquitted of negligent homicide charges in late 2001 and had left Cincinnati Police for a new job there.

Evendale didn't have a big police department. What if, she thought, the officer sitting in the car behind her was Roach?

She gripped the steering wheel and looked in the rearview mirror, trying to get a better look. She started to shake, then to cry. She looked again in the mirror but could only see a figure behind the windshield.

She said the officer appeared to be checking the monitor in the cruiser, probably running her license, and then looking up again and again at her car.

Leisure kept her hands on the steering wheel, tears running down her face.

The officer never got out of the car. The cruiser just pulled away, merging back onto the highway, leaving her there on the side of the road, trembling.

She never learned if the officer was Roach, or just another officer who recognized her name and didn’t want to deal with a traffic stop involving Timothy Thomas’s mother.

But she did learn she’d had enough. She needed to get out of Cincinnati.

“I was so tired of being afraid,” she said. “I was so tired of hurting.”

Another death in another city

Leisure moved to Chicago in 2003. She had family there, but mostly she needed to be in a place where no one other than relatives knew her or Timothy’s name.

From afar, she watched Cincinnati move forward with police reforms. She kept in touch with family here and with her lawyer. And she felt, finally, that both she and the city she’d left were making progress.

Then, last summer, she watched the video of a police officer in Minneapolis press his knee on the neck of George Floyd until he died.

By 2020, Leisure said, her views of police had shifted, at least a little. She no longer viewed them all the same, as nameless, faceless brutes who abused their power. She’d met and spoke to officers and had come to believe many were doing the job for the right reasons.

But that video, it brought it all back. “I felt a lot of anger,” she said. “I still do.”

She wasn’t surprised when Cincinnati, like cities across the country, erupted in protests and unrest. As in her son’s case, George Floyd, quickly became a symbol, a rallying cry. His face, like Timothy’s, appeared on signs and shirts and memorials.

Unlike Timothy’s death, though, Floyd’s was captured on video and circulated on social media. Leisure immediately thought about his family. She knew what it was like for her family in 2001, but what about now? What’s it like when the entire world knows your dead son’s name?

“I can only imagine how that family felt,” Leisure said. “It hurts your soul.”

Remembering and reclaiming a lost son

At the end of every July, the weekend after Timothy’s birthday, Leisure and her extended family gather in Chicago for a party.

They call it “Tim’s Day,” a celebration of his life.

Relatives come from all over the country. It’s a family reunion, really, but the star of the show is Timothy. Leisure’s other children are there, and so is Tywon, her grandson.

She tries to avoid lectures about policing, or warnings about driving. Instead, she and her family tell stories about her son. They talk about his light-up-a-room smile, about his sense of humor, about what he might be doing today if he was still with them.

“So bright was his future,” Leisure said. “I think about that a lot.”

It’s a great day, she said, because everyone her son loved most is there, laughing, sharing stories. When they say his name, he’s not a symbol. He’s a son, a brother, a father. He’s just Timothy Thomas.

And for the day, at least, he belongs only to them.

Source link