Editor's note: This story was originally published in 2018.

It feels special, even from a distance.

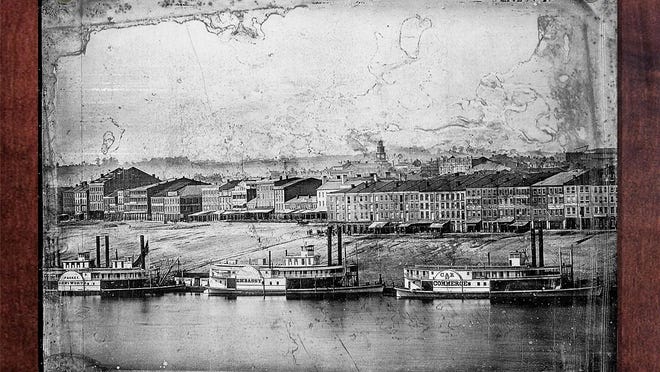

We are standing a couple feet in front of Cincinnati 170 years ago, in front of an eight-plate panorama called the "Daguerreotype View of Cincinnati. Taken from Newport, Ky."

Eight plates – each a couple inches bigger than an iPhone X – capture a segment of two miles of riverfront. The series hangs on the back wall of the Cincinnati Room of the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County, the caretakers of the rare piece for the last century.

It feels special, we think, because we suddenly feel close to our Queen City just a few years after her coronation. When Cincinnati was a boom town on the edge of the American West.

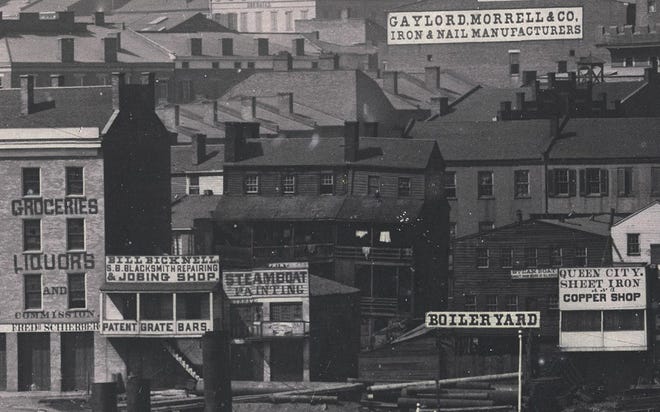

The remarkable details of the photographs make it a portal: Photographers Charles Fontayne and William S. Porter captured shops and factories, farms and steamboats with incredible crispness and clarity.

There is a squat skyline, no more than a couple stories high, punctuated by a couple church spires. The surrounding hills are stripped of trees. Piles of lumber line the shore.

As we study the image, we imagine ourselves standing on that muddy shore. Hanging laundry on a porch. Grabbing a whiskey in a tavern.

Even though this is a Cincinnati from seven generations ago, still a decade before the Roebling Bridge, 40 years before Music Hall, a hundred years before Carew Tower.

We didn't stay in the past for long, though.

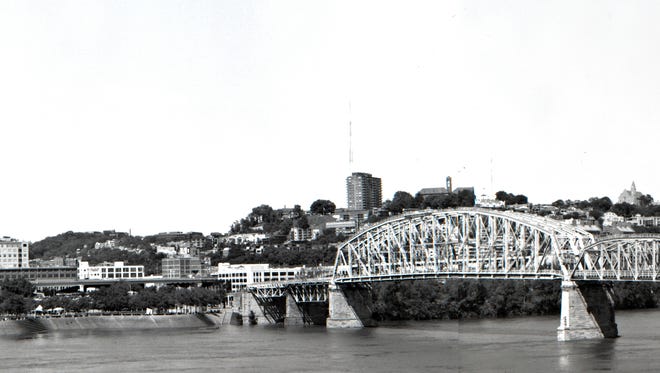

This panorama, the oldest of any American city, still made us ask some questions about today: What does the Cincinnati panorama of 2018 look like now? And what does it say about us?

But first, we had to figure out when and how we would recreate it.

We started with the when. That would be Sept. 24.

Previous researchers determined that was the day the panorama was shot using records like the weather and river levels reports, as well as the national press coverage the daguerreotype earned at the time. (Remember: This was the first panorama taken of a city in the United States. It would have been a technological and artistic wonder akin to how "Avatar" forever changed audience expectations of what a 3-D movie could be.)

So, we knew the date. Next, the location.

The photographers already gave that detail away – Newport is in the title. And based on the perspective of the plate, it had to be where Newport on the Levee is today. (We'll explain how we lined up the location later on. We promise.)

We headed to the Newport Aquarium on the afternoon of September 24. (More on the time of day later, too.) The aquarium is about the same height as a couple-stories high 1848 rooftop, a height typical for the time.

But what we couldn't control? The weather.

We stood under a couple of umbrellas on the roof. The rain still threatened our mid-century Speed Graphic film camera. We were rushed, we were not satisfied.

We really couldn't risk getting that Speed Graphic – and the film – wet. The water would ruin both. And we had a reason for not using a digital camera even though it would have, frankly, been easier to use, to just point and click.

So we went back four days later, when it was dry and sunny.

Funny thing, it turns out, a complicated and clunky, 70-year-old film camera actually does a better job when it comes to resolution.

And get this: The images made today by the state-of-the-art equipment does not compare to the quality of those made by the 1848daguerreotype process. Yup,even if we spent six figures on the best camera we can get our hands on, our panorama would not look as good as what Fontayne and Porter did 170 years ago.

How good is daguerreotype good? We could zoom in 30 times on the Cincinnati Panorama, and the details would just get clearer with each click.

How clear is daguerreotype clear? The plates could be reproduced to hang on a 17-story-high building and still look amazing from the street.

Simply put, the daguerreotype's advantage is that is larger, so it can capture more of an image and more light. The details feel more real because of that. Our modern cameras instead use tiny squares of colors called pixels to fool the eye into thinking we are seeing an image.

We couldn't, however, use the daguerreotype process to do our 2018 series. It requires expert skill, would be expensive – it uses silver-coated copper plates – and most importantly, it is incredibly unsafe.

Invented in 1839 by French scenic painter Louis Daguerre, the daguerreotype is considered the first publicly available photographic process. His innovation?

Images could be created in 20 minutes or so instead of hours. Photography was just a couple decades old at the time, so this was a huge deal. (The word "photography" was actually coined the same year Daguerre shared his invention with the world.)

But the secret of his innovation was also secretly toxic: Plates were developed using deadly mercury vapor.

For the1950s-ish Speed Graphic camera, all we had to do was find a local studio that could develop the film. After a week of processing time, what we got back amazed us.

In a series of black-and-white photographs, we captured a community that spans two states, connected by six bridges. We see skyscrapers emblazoned with corporate logos. We see parks lining the river and softening the hillsides. We see apartment high-rises and three sports stadiums. And if we zoom on the composite image using our computers, we even see a person sitting on the steps of the Serpentine Wall.

Back at the library, we can also zoom in on the "Daguerreotype View of Cincinnati. Taken from Newport, Ky." We can, in fact, find people standing on the shores of the Ohio River in 1848.

Staff there have set up a large digital touchscreen that allows us to look more closely at each plate. There is an online version, too, through the library here. On that website, researchers also added more information on what we are seeing and why it matters.

The interactive experience actually uses photographs taken with a microscope. A few years ago, conservators at the George Eastman House in New York used that technology to determine what was a detail and what actually a blemish, dirt or damage that needed fixing in the 1848 panorama.

The microscope reveals jaw-dropping specificity, like a carriage wheel's spokes and a man's top hat.

We no longer have to imagine ourselves in that image, pretending to be a citizen of 19th century Cincinnati. It's like we are inside of it.

So, the daguerreotype somehow gets even more special, up close.

Exploring the piece, down to the molecules almost, also helped us with our contemporary re-creation.

Here's a closer look at the clues we discovered and how we used them today:

This is the clock tower of what was the Second Presbyterian Church Downtown. If we look at the plate, the size of the clock is same as a head of a pin. When we look closely, the time says 1:55 p.m. So, we know that middle plate was taken at exactly 1:55 p.m.

Information about exactly how, when and why photographers Charles Fontayne and William S. Porter took the panorama has mostly been lost to time. However, researchers have been able to figure out exactly the day – Sept. 24, 1848 – based on a variety of clues.

One big one?

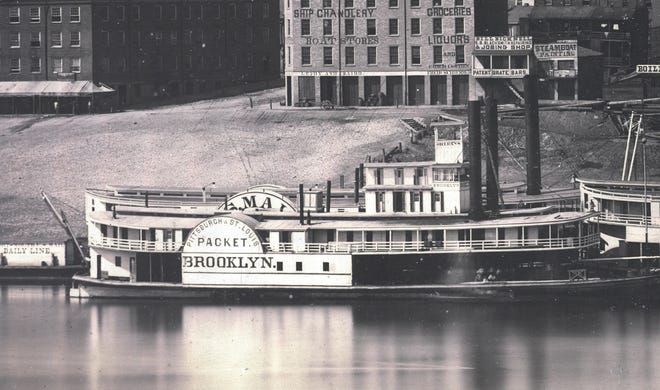

The names of the riverboats docked on the shore. Meticulous records were maintained of river traffic, even printed in the newspapers. Steamboats also didn't have long lifespans, maybe five years. They tended to be badly constructed and poorly maintained.

So, these boats were not there, all at the same time, more than once, according to the records.

A man sits in his horse-drawn wagon along the edge of the river on the Kentucky side.

It's believed that Fontayne and Porter chose to photograph the riverfront on a Sunday when people would not pack the riverfront for work and travel. People in motion appear as blurs because of the six- or seven-second exposure time for a daguerreotype.

The Public Landing was its busiest in the mid-19th century. Steamboat economic dominance established Cincinnati as a frontier boom town.

A city of around 115,000 at the time, it was the fastest growing city in the country. (And recently crowned the Queen City.) The burgeoning industries of pork-packing, metalworking, boat building and furniture making kept them employed.

Manufacturing then lived by the river.

Signage of the shops, stores and bars catered to that work and the worker. There are blacksmith and steamboat painters. And a shop with groceries and liquors.

Other plates reveal additional dimensions of the city's character, a place of pride and progress. There are schools and universities, churches and an art gallery. The observatory, too.

Of course, schools and universities and churches and galleries arestill here. But the buildings they occupied are no longer part of our skyline.

There is actually only one structure featured in the 1848 photographs that still stands today. (No bridge even crossed the Ohio River.)

Back then, it was called the Longworth Mansion. Today, it's the Taft Museum of Art.

The panorama captured two miles of riverfront and city that has undergone massive change.

So, we had to get creative to find current landmarks to orient our 2018 re-creation. Take the seventh plate, shown here. The two trees in the top right corner are no longer there.

In just 11 years, they would be gone from the ridge. The Church of the Immaculata now stands in their place.

Special thanks to James Mainger from the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County for showing us and explaining the Cincinnati Panorama.

Source link