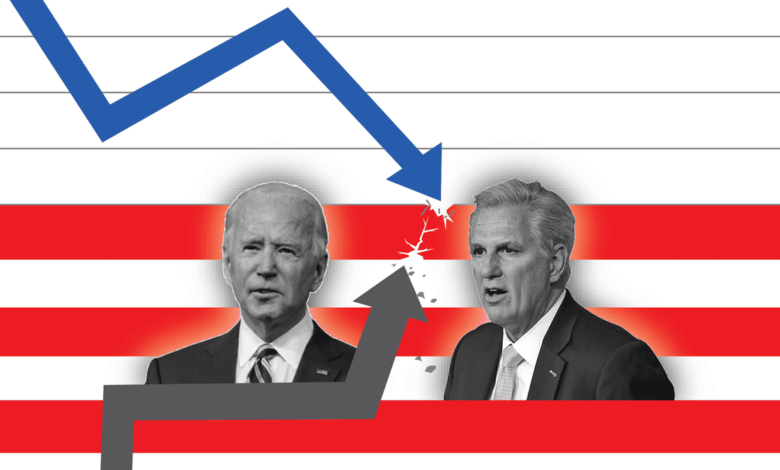

Republicans and Democrats have been in a standoff over raising the debt ceiling, and if they don't reach an agreement soon, economic catastrophe could quickly ensue. Maybe even as early as June, according to Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen.

That sounds pretty dire, with the clock ticking quickly toward that date. Republicans are demanding deep spending cuts and other policy changes in exchange for raising the debt limit, but Democrats refuse to tie spending negotiations to debt ceiling talks.

This all sounds like a recipe for disaster in financial markets, but so far, the stock market has managed to chug along, seemingly fearless and helping to buoy retirement nest eggs. However, other asset prices tell a different story.

Let's take a look.

In a letter on May 1 to members of Congress, Yellen warned that failing to suspend or raise the debt limit soon will result in "serious harm to business and consumer confidence, raise short-term borrowing costs for taxpayers, and negatively impact the credit rating of the United States." She suggested that could come as early as June 1, the so-called X-date, when the nation is unable to pay all its bills.

If the U.S. enters a "technical default," which is as an extended period of nonpayment of some or all U.S. financial responsibilities and is less serious than an actual default in which the country runs out of money and stops paying all its obligations, economists expect a recession to come quickly.

"A technical default would double the current unemployment rate of 3.4% to near 7%, tip the economy into recession within six months," said Joseph Brusuelas, chief economist at RSM US LLP, an independent audit, tax and consulting firm. As a result, he expects inflation to recede for a short time before resurfacing amid strong government spending.

About half of American households own stocks either directly or indirectly through mutual funds or 401(k) accounts, so a stock market decline would reduce household wealth across a large portion of America and affect everything from college savings plans to retirement plans.

So how’s the debt ceiling battle affecting stocks? So far, the S&P 500, the broadest measure of the stock market’s performance, is up about 8% year to date. The market is focused more on hopes that inflation and the economy will cool enough that the Federal Reserve will stop raising interest rates, and maybe even begin lowering them later this year. Corporate earnings have also been stronger than expected in the first part of 2023, helping to support stocks and keep retirement funds in the green.

If a default happens, Yellen said in a speech to the Independent Community Bankers of America on Tuesday, we could see "a downturn as severe as the Great Recession," lose more than eight million jobs and 45% in the value of the stock market, "wiping out years of retirement and other household savings. If that sounds catastrophic – that’s because it is."

What about the 2011 debt ceiling fight that brought the U.S. to the brink of default? Does that say anything about what stock investors should expect? '

In 2011, Congress finally agreed on a debt ceiling increase on the day Treasury had marked as the X-date, Aug. 2. But stocks weren't in the clear. Just days later, ratings agency Standard & Poor’s downgraded the U.S. long-term credit rating, even though the U.S. never missed a payment. The agency cited political brinksmanship and concerns about the ability of the U.S. to manage its debt.

That was tough on 401(k)s. The stock market dropped more than 15%, said Gregory Daco, chief economist at EY.

Ultimately, household wealth fell by $2.4 trillion between March through June that year and July through September, and retirement accounts lost $800 billion, Treasury said in a report. The S&P 500 index didn't recover until 2012, it said.

Stifel Chief Washington Policy Strategist Brian Gardner sees the chances of a credit rating downgrade this time as "relatively high." He said it's possible ratings agency Moody’s, which now gives the U.S. its top rating, might modestly lower its rating, while S&P could trim its rating again. S&P never bumped America back to its top rating after 2011.

Yes. Foreign investors who lend money to the U.S. government, which is considered one of the world’s safest investments. Demand from these investors for short-term U.S. debt, or Treasury bills at the Treasury's regular auction fell off on May 4, days after Yellen first suggested the government may not be able to pay its debt on June 1 or within a few weeks of that.

Why?

Those bills come due on June 6, shortly after the June 1 deadline after which Yellen says Treasury could default on its debt. That may have scared foreign investors away. Foreign investors are important for the economy because they help absorb mounds of U.S. government debt, which allows the U.S. to borrow at lower interest rates. However, they took only 42.1% of the T-bills in that May 4 auction, less than the 59.4% in the previous auction and the 63% average, according to Action Economics.

If people lose confidence the U.S. will pay its debts on time and shun U.S. government debt, Treasury yields will rise and raise financing costs for the government and consumers.

Yes. Not only were there fewer foreign investors at the May 4 T-bill auction, but those who did buy the T-bills demanded a higher interest rate payout to hold the debt.

The yield, or interest rate, on those auctioned T-bills jumped to a record high of 5.84% and was higher than the expected 5.8% rate at the bid deadline, showing investors demanded the U.S. pay more interest because the buyers perceived a greater risk to their investment.

On the flip side, the government is paying more to borrow. If rates continue moving higher, the cost to finance the government's activities gets more expensive, which can create a larger fiscal hole.

In 2011, the last time the U.S. came to the brink of default, yields rose but not quite as quickly and as steeply as this time. Back then, the nation's debt was much smaller, and no one really expected a default was possible, Arvind Krishnamurthy, a finance professor at Stanford business school, said in January.

"The main issue that arose in 2011 was that bondholders were concerned that principal payment may be delayed on a one-month treasury bill until the debt ceiling issues resolve," said Krishnamurthy. "Delayed, not default — that’s what investors were thinking."

This time, though, some have moved on to default. Gardner sees the chance for a technical default as still "relatively high" even though there've been signs of progress.

The practical deadline for a deal may be May 26 if Yellen is correct and the X-date falls in the first week of June, Gardner said.

"Even after a deal is reached, it needs to be put into legislative language and members of the House and Senate will need a few days to review the bill before voting on it," he said. "With Congress scheduled to be out of session the week after Memorial Day, an agreement probably needs to be in place before the holiday weekend. If needed, Congress could pass a short-term suspension of the debt ceiling in order to allow for time to vote on the bill, but this probably needs to happen before the Memorial Day weekend."

There's a possibility the X-date could be closer to mid-June instead of the first week of June, Yellen noted. If the government has enough cash to make all payments through June 15, quarterly tax receipts could provide enough revenue to push the X-date back several weeks into July.

"Under this scenario, a temporary suspension may not be necessary since the White House and McCarthy's team would have time to reach a deal," Gardner said.

Published

Updated

Source link