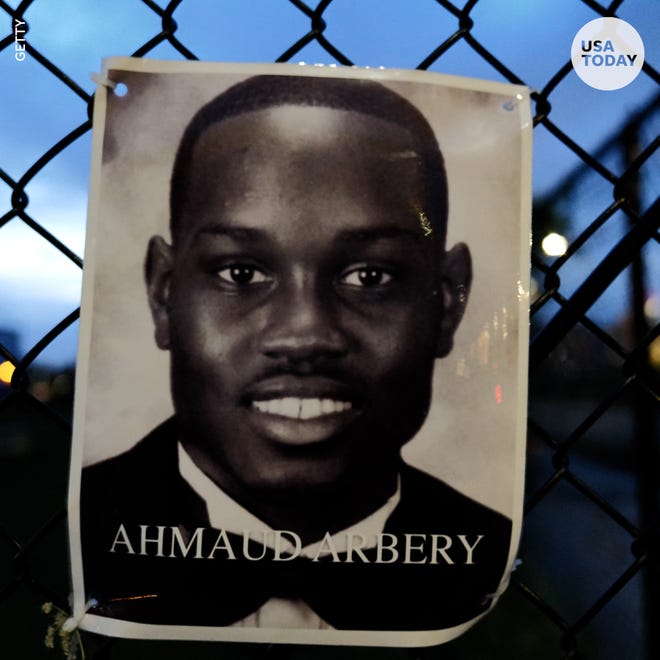

On Jan. 7, Travis and Gregory McMichael and William Bryan, three white men, were sentenced to life in prison for the murder of Ahmaud Arbery, a 25-year-old Black man.

In 2020, the McMichaels chased down Arbery while he was out for a jog. Travis McMichael shot him dead, and William Bryan filmed the encounter. Gregory McMichael is a former Glynn County, Georgia, police officer and former investigator for the county prosecutor’s office.

Lawyers for the McMichaels and Bryan claimed the men were executing a citizen’s arrest and that they thought Arbery fit the description of a neighborhood burglary suspect.

Opinions in your inbox: Get a digest of our takes on current events every day

Many are wondering whether convictions in Arbery's murder – similar to convictions for the murder of George Floyd and the manslaughter of Daunte Wright (both of whom were killed by police officers) – are bringing the nation significantly closer to fulfilling the main goal of the Black Lives Matter movement: more accountability and justice for Black bodies.

Although I would not go this far yet (police killed more than 1,000 people in 2021), these cases do have noteworthy similarities and differences.

The McMichaels and Bryan operated as if they had a license to kill. They jumped to their own conclusions and felt emboldened to take the law into their own hands. They engaged in stereotypes about the criminal culpability of a young Black male involved in a normal activity.

Research documents that some white people have the same psychological response to seeing the faces of Black men as they do to snakes and spiders. The juries in all three cases were overwhelmingly white.

MORE FROM RASHAWN RAY:Potter and Goodson cases tell us more about why people are killed by police

Meaningful realities are found in some of these cases that speak to what it might take to increase transparency, accountability and justice – particularly related to criminal sentencing outcomes.

Jurors in the McMichaels and Bryan case, and in the cases of Kim Potter (who killed Wright) and Derek Chauvin (who killed Floyd), witnessed the killings on video. Technology has made what used to happen only in the dark come to light.

Contrast that to the killing of Florida teen Trayvon Martin, for which there was no video. In the Martin case, George Zimmerman's vigilantism was not perceived as a threat, and he was not convicted.

The Georgia Bureau of Investigation handled the charges and prosecution of the McMichaels and Bryan. State-level oversight also occurred in the cases for the killings of Floyd and Wright.

The trial for Arbery's murder almost didn't happen. But a video of the murder recorded by Bryan helped to spark a broader investigation and state-level involvement. Ultimately, former Glynn County District Attorney Jackie Johnson was charged with obstruction.

Defendants in the killings of Arbery and Martin claimed self-defense. The incidents occurred in stand-your-ground states. In theory, stand-your-ground laws make sense. A person should have the right to defend themselves. In practice, however, the perception of who has that right is too often skewed by race and driven by stereotypes about Black bodies.

COLUMN:As a young Black man, I was a victim of police brutality. That's why I became a cop.

More than 30 states have some form of stand-your-ground or castle doctrine laws. And they are all fairly recent.

Florida became one of the first states to enact such a law in 2005. Before then, individuals in most states were required to “retreat before using deadly force” if it was safe to do so.

According to The Coalition to Stop Gun Violence, 600 additional homicides (like the killings of Arbery and Martin) are linked to stand-your-ground laws each year.

In a Florida study, nearly 70% of stand-your-ground cases where the defendant was not charged or was acquitted, the person who was killed didn't have a weapon. And, even when stand-your-ground laws are not used as a viable defense, perceptions of what self-defense is and should be has expanded.

These statistics are part of the reason people have been nervous about the outcomes of trials involving Black victims. And why people are surprised about the harsh sentences given in the most recent trials involving white assailants.

Has this country fully answered the call of Black Lives Matter? No.

But if people are to be held accountable for racially biased killings – leading to a nation that ultimately ends racialized vigilantism – stereotypes about criminal culpability and victimhood need to change.

Rashawn Ray is a senior fellow at The Brookings Institution and professor of sociology at the University of Maryland. Follow him on Twitter: @SociologistRay.