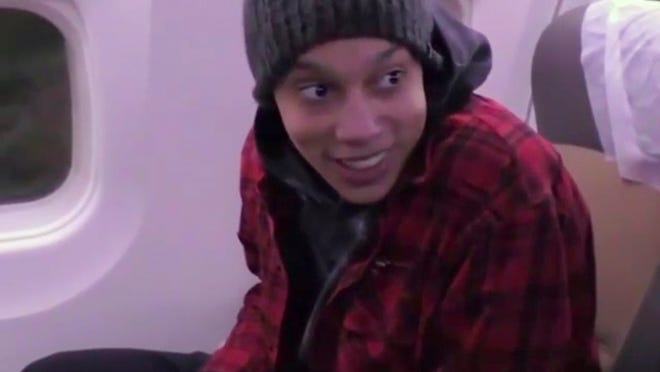

After the two prisoners walked past each other on the airport tarmac in Abu Dhabi – American basketball star Brittney Griner and Russian arms dealer Viktor Bout, nicknamed the "Merchant of Death" – this week's high-stakes exchange between the U.S. and Russia was finally complete.

That tense moment came just eight months after the Biden Administration swapped Konstantin Yaroshenko, a Russian pilot and drug smuggler, for ex-U.S. Marine Trevor Reed, who had been held in Russia on espionage charges since 2018.

Both became part of a history of delicate and difficult prisoner swaps with Russia, Iran and other adversarial nations. Such swaps, including the one for Griner, have been deeply controversial, yet the tradition in the modern era stretches back to the return of a downed U2 spy plane pilot in 1962.

More:Prisoner swap negotiations were 'painstaking, extraordinary'

Experts say each case is unique and often requires intricate negotiations and difficult choices.

“Often, the price we pay for bringing our fellow Americans home to their families is unseemly, but it is the right thing to do,” Bill Richardson, a former United Nations Ambassador who has helped secure the release of U.S. detainees in Cuba, North Korea and elsewhere, said in a statement.

More:A complete timeline leading up to WNBA star's release

How do prisoner swaps work?

Prisoner exchanges have occurred throughout history with soldiers captured during war.

But peacetime swaps of civilians, like the one involving Griner, are far less predictable.

They may involve Americans held hostage by terrorist groups or U.S. residents deemed to have been wrongly detained under foreign criminal charges.

Detainees, such as two U.S. veterans captured while volunteering in Ukraine this year, are viewed as bargaining chips, according to Melvyn Levitsky, a professor of international policy at the University of Michigan and a retired U.S. ambassador.

More:Americans held captive by Russian separatists in Ukraine have returned to the US

The U.S. State Department's special presidential envoy for hostage affairs handles cases of Americans who are kidnapped and those the U.S. considers to be detained wrongfully or unlawfully overseas, Danielle Gilbert, Dartmouth College professor and top expert on international hostage situations, told USA TODAY.

Also helping is a coordinated response team of diplomats, intelligence agents and law enforcement officials. That team was put in place beginning after prisoners including journalist James Foley and others died as captives of the Islamic State. In that case and others, relatives of detained Americans had complained that American policies prevented them from effectively working to free their loved ones.

More:An American is detained or goes missing abroad. What happens next?

Independent negotiators or well-connected intermediaries can also work on behalf of the captured Americans.

For example, Richardson's non-profit agency, the Richardson Center, has worked to win the release of detainees including several Americans held by Colombia’s Revolutionary Armed Forces and the 2009 release of a U.S. journalist sentenced to prison in North Korea.

Ultimately, the State Department and White House often make the decisions about the trades, Levitsky said.

“It depends upon what county we’re dealing with and what that relationship looks like. There’s not a cookie-cutter solution,” he said.

How common are prisoner swaps today?

Gilbert said situations where the U.S. is trying to free an American from wrongful criminal detention by a nation, rather than a terrorist group, have increased since 2015.

“The phenomenon is growing,” she said, estimating there are now a handful of prisoner exchanges each year.

Former President Trump made several high-profile efforts to free Americans. In 2019, for example, Trump publicly pushed Turkey’s president Recep Tayyip Erdogan to release North Carolina pastor Andrew Brunson.

That same year, the State Department said it had helped release more than 180 Americans since 2015.

Today there are 60 U.S. nationals and U.S. lawful permanent residents held in publicly disclosed hostage and wrongful detention cases in 18 countries including Russia, Iran, China, Venezuela and Mali, according to the James W. Foley Legacy Foundation.

Among them is Paul Whelan, an ex-Marine from Michigan, arrested in Moscow in 2018 and accused of spying for the U.S. government. His family has said he was a security director for an automotive-parts company and was in Russia for a wedding.

Experts said that while Russia refused to include Whelan in the swap for Bout, the publicity surrounding the case may increase pressure and efforts to win his release through some kind of exchange.

What are some notable prisoner exchanges?

One of the best-known happened in 1962, a swap later portrayed in the Steven Spielberg Cold War movie “Bridge of Spies.”

In that case, the U.S. won the release of U2 spy plane pilot Francis Gary Powers, who was shot down and captured by the Soviet Union, in exchange for Rudolf Ivanovich Abel, a Soviet intelligence officer.

Other Cold War exchanges included trading U.S. reporter Nicholas Daniloff, then a Moscow-based reporter for U.S. News & World Report, for Gennadi Zakharov, the Soviet employee of the United Nations arrested for allegedly handing over money to a contact for classified U.S. Air Force documents.

More recently, in 2014 during the war in Afghanistan, the Obama Administration released five Taliban prisoners for Sgt. Bowe Bergdahl, who had been held by the Taliban after leaving his base.

Two years later, in the context of the U.S.- Iran nuclear deal, the U.S. won the release of journalist Jason Rezaian, imprisoned on espionage-related charges, in exchange for Iranians who had been charged with violating U.S. sanctions.

In September, two American veterans held captive by Russian separatists in Ukraine since June returned after a Saudi-brokered swap with Russian-backed separatists that included eight other prisoners from four countries.

Are prisoner swaps controversial?

U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken in July said the U.S. had made a "substantial offer" in exchange for the Griner and Whelan.

But White House press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre and senior administration officials said this week that Russia would not engage in good faith negotiations for Whelan.

"It was either Brittney or no one at all," Jean-Pierre said.

Some critics have argued that Bout’s crimes are mismatched with Griner’s alleged crimes — possessing cannabis vape cartridges. Bout, 55, is a former Soviet military officer, was serving a 25-year prison sentence for conspiring to kill Americans, acquiring and export anti-aircraft missiles and providing material support to a terrorist organization. Bout claimed he was innocent.

Gilbert said while Bout is very prominent, others traded by the U.S. in exchanges have been convicted of crimes such as violating sanctions against other nations or involvement in cyber crimes.

Some also argue that exchanging prisoners could encourage other countries to detain Americans, she said. While it’s not clear yet that’s happened, she said, “That’s a live debate. And I think that’s a legitimate concern."

Tulane University political science professor Chris Fettweis said in a statement that – despite the criticism by some – he believes Griner's release was a positive outcome.

“Griner was a political prisoner. We got her home. It’s a good day, no matter how much some people want to inject some moral ambiguity into it,” Fettweis said.

Chris Kenning is a national reporter. Reach him at [email protected] and on Twitter @chris_kenning.