As Zina Wilson sat in front of her computer in her suburban Ohio home last year, she decided: You have ripped off the wrong family.

Wilson, 51, was fed up with her niece receiving eviction notices for apartments in Las Vegas she had never rented, about receiving notices from collection agencies for Wi-Fi in cities where she had never lived.

She would fight back in the online world, where she soon learned nothing can be trusted as real. Her search led her to gangs and criminals. Fearing for her safety, she agreed to tell her tale under one of the nom de plumes she used in her online research.

USA TODAY NETWORK

Online identity theft scams flourished during the COVID-19 pandemic, ensnaring 1 in 6 Americans and leading to $52 billion in losses last year alone, according to Javelin Strategy & Research.

Despite having no experience in online investigations, Wilson became obsessed with the case. She came to see it as a righteous fight for justice against a criminal scheme that she would learn, clue by clue, sprawled across the country – one she believes involves dozens of victims.

“I will not let this go,” Wilson said. “It’s about my niece, but I hate when people do the wrong thing ... knowingly stealing and ruining peoples’ lives.”

For individual victims, cleaning up a fraud case on average takes 16 hours of effort, Javelin estimates, with no guarantee of recouping losses. And identifying your perpetrator so criminal charges can be filed? Good luck.

Wilson’s dogged sleuthing over 18 months left her among the lucky ones. This fall, she received the email she had been waiting for: “Wanted to let you know the good news,” a detective wrote in September, attaching a screenshot from the Clark County, Nevada, inmate portal.

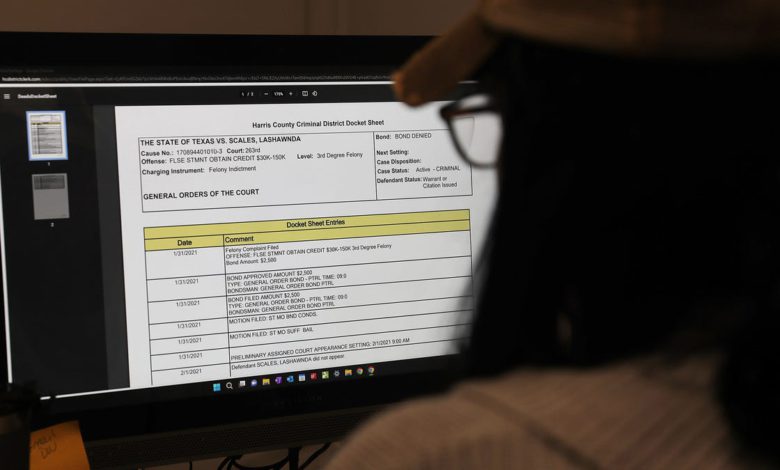

Lashawnda Scales was behind bars, held on forgery charges related to a scheme to live a life of luxury by stealing the identity of unsuspecting victims.

Targeting Wilson’s niece was her biggest mistake.

Nariah Cunningham walked out of her home in Las Vegas and hopped into a waiting car. Within minutes she was pulled over and arrested by Las Vegas Metropolitan Police, who had been staking out the property.

Cunningham wasn’t her real name – just one of the many aliases used by Scales, 29, who was leasing the $500,000 house in yet another person’s name, among the people whose identity police say Scales stole.

When arrested in September, she left the house keys in the car and told detectives she had no connection to the property and didn’t know anything about it, according to police records.

Inside the three-bedroom house, detectives discovered what they called a “forgery lab” – three computers, cellphones, printers and laminators. They found driver's licenses from Arizona, California, Florida, Nevada, Utah, Texas – all bearing Scales’ face but the names of others.

They also found three Social Security cards linked to stolen identities, seven credit cards with mismatched names, and a stack of mail sent to various women at the raided home’s address.

Las Vegas police accuse Scales of scamming at least 13 people. Wilson believes there are many more.

Police say Scales was running a luxury rental scheme and bulldog puppy mill. She also stands accused of fraud in Texas for purchasing high-end cars with stolen credit.

Local police often are ill-equipped to help with identity theft, and federal investigators typically take on only large-scale fraud. But investigators in the Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department’s financial crimes division got a head start when Wilson brought a mountain of evidence to their door last February.

By then, she had been turned away by at least five other investigative agencies.

Trouble began for Wilson’s niece when odd paperwork addressed to her started landing in her parents’ mailbox: You’re delinquent on your internet payments, and you’ve failed to return our equipment.

She knew something was off: The account with Cox Communications was connected to internet service in Las Vegas, more than 2,000 miles away from where she lived.

In the months that followed, the 26-year-old began receiving threats from collection agencies, which called, texted and sent her notices demanding overdue payments she knew she hadn't missed. Property records indicate that she was evicted from at least seven homes in two years and owed about $30,000 in back rent. None of that poor track record was hers either.

“It’s been terrible,” she said, speaking to USA TODAY on condition of anonymity. She’s afraid of being scammed again, anxiously waiting for the next eviction notice to hit her credit report.

Provided

The woman turned to her mother and aunt for help cleaning up her credit and stopping the fraud. That turned out to be harder than it seemed.

Real estate rentals were at the center of this particular scheme, the investigation would later reveal.

Scales is accused of printing driver's licenses with her face and the name and address of the 26-year-old in Ohio. She used that ID card to submit rental applications around Las Vegas, police say, then sublet the rentals to others.

I’ll just stay awake at night worrying about it. Identity theft is so weird. There’s no clear path for victims and I don’t know how my life will go after this.

In August, for instance, a Facebook post by Scales advertised a five-bedroom home for rent in the Summerlin South area of Vegas, with a pool and Jacuzzi, for $4,800 a month. The post said she’d charge $9,470 for the deposit and first month’s rent, not including her fee. “Move in Monday,” it urged.

Police say Scales would sublet to acquaintances and strangers who couldn’t qualify for a lease on their own. While she pocketed the deposit and rent, they say, the renters lived in the apartments for a few months, trashed them and skipped out without ever paying the rent.

Landlords and real estate companies eventually would file eviction paperwork – of course naming the person on the ID, the 26-year-old in Ohio, instead of Scales.

A similar situation allegedly played out around the same time for another young woman, a teacher also from Ohio.

That woman, who asked to be identified only by her first name – Caitlin – says she learned in late 2020 that someone had opened a new T-Mobile cellphone account in her name. Then she received notice of a car rented under her name and never returned.

“The people she rented the car from called me up and asked for the car … that I didn’t have,” said Caitlin, now 27.

Like Wilson’s niece, Caitlin’s credit score took a beating. Despite her attempts to freeze her credit and appeal the charges, when she moved earlier this year, she had to get her father to co-sign her lease.

“I’ll just stay awake at night worrying about it,” Caitlin said. “Identity theft is so weird. There’s no clear path for victims, and I don’t know how my life will go after this.”

Wilson, the Ohio aunt, is a fast-talker who makes liberal use of emojis in her texts. She describes herself as someone who’s always trying to help others, “beating the bad guys and doing what I need to win.”

She couldn’t watch her niece suffer anymore. So, after doing almost a year of legwork on her laptop, she took a trip to Las Vegas in early 2022 to try to get to the bottom of things.

Wilson had asked her niece to sign over power of attorney so she could visit rental offices and pull paperwork from landlords on the young woman's behalf. She assumed she could simply correct the errors so her niece could move on.

“I just kept hitting roadblocks and rude desk staff that just smirked and told me it was a police issue and they couldn’t help,” Wilson said.

Yet that’s when the case broke open, speeded up and grew.

At Ohana Realty Group, Wilson requested paperwork from the lease of a $1,900 apartment that had recently gone through an eviction. That’s where she came across Caitlin: A rental application in her niece’s name listed Caitlin as the emergency contact.

It included a copy of the fake Ohio ID with her niece’s address and an unfamiliar photo. The file suggested that the applicant had bought a renter’s insurance policy with Allstate – also in Wilson’s niece’s name.

When Wilson tracked Caitlin down in Ohio, she heard a familiar story: Caitlin first began receiving odd mail about new accounts, then her credit was hit with new inquiries, month after month.

One document submitted to the rental agency indicated that the applicant had even created a fake work history for Wilson’s niece.

A copy provided to USA TODAY shows what Wilson later learned was a forged employee verification document for GlaxoSmithKline, with an annual salary of $70,200. The rental application included paystubs, featuring Wilson’s niece’s Social Security number.

Wilson submitted the documents to Las Vegas police but didn’t hear back. USA TODAY shared those documents with GlaxoSmithKline independently.

“Thank you for bringing this to our attention,” Kathleen Quinn, GSK spokesperson replied in an email. “We can verify these are not legitimate GSK documents, and have notified our internal cyber security team and law enforcement.”

One nugget of information on the rental application appeared to be real: a phone number. Using some free online tools, Wilson tracked down a name at last: Lashawnda Scales. Some more Googling indicated Scales had been convicted of forgery before.

Wilson celebrated every sliver of new information.

“I’d yell out or … do a little dance like scoring a touchdown,” she said. “I would immediately text and call my family to tell them the latest.”

Wilson wrote letters, emails and called the Federal Trade Commission, attorneys general, the Small Business Association, police in Ohio and Las Vegas, and the FBI. No one responded with a solution, if they responded at all. Many sent automatic replies.

A Las Vegas television station had solicited tips about wrongdoing, so she tried them. Nothing.

Exasperated, Wilson took her files and other evidence in person to Las Vegas police’s northeast command outpost. They told her to contact the FBI.

She went to the department’s five-story headquarters, took a number and waited in the lobby for 45 minutes. At the counter, she remembers being told: “Sorry, you need to call authorities in Ohio.”

She could have given up and flown home. Instead, while strategizing what to do next in her car in the parking lot, she spotted and buttonholed a plainclothes officer coming off his shift. He agreed to give her contact information for the department’s financial crimes unit.

At last, someone was listening.

Armed with a name, Detective Taylor Webb, Wilson flooded the Las Vegas police department with everything she had found. Webb also used the cell number from the rental application to tie the fraud to Scales, and he tracked down her social media accounts.

The accounts use a fake name, Nariah Cunningham, but Scales hadn’t bothered to change the URL: shawnda18theboss.

Webb declined to comment on the investigation, but the department sent a written statement outlining their findings.

“Ms. Scales would apply to rent the properties using the fraudulently obtained personal identifying information, after obtaining approval from the rental company she would then post the property on social media sites detailing the legitimate cost of the property. In the post she would advise that the 3rd party renter (often those who were ineligible to rent due to credit issues or criminal history) were responsible for paying the deposit, monthly costs, and her ‘fee.’ Ms. Scales’ ‘fee’ is where she profited from the alleged criminal activity.”

Even though someone finally was taking her tips seriously, Wilson didn’t stop investigating. Evidence of fraud targeting her niece continued to build.

Wilson contacted another apartment manager, Waterton, which in January 2022 had rented out a one-bedroom apartment for $1,170 at the Paisley & Pointe at Centennial Hills to someone posing as her niece. The application paperwork listed the same fake job at GSK.

She visited Waterton in person and brought the fraud to the company's attention, but emails between Wilson and Waterton suggest that the most visible action the company took was to evict Scales – which of course boomeranged back to Wilson’s niece’s credit report, according to Wilson.

I absolutely went down the rabbit hole. I got really deep in the weeds, almost obsessive.

The rental company sent the outstanding debt, $7,634, to collections through a company called RentDebt. A Waterton spokesperson declined to answer USA TODAY’s questions about the case.

Wilson continued to send Waterton emails demanding a fix. She kept emailing Las Vegas police as well as her local Ohio sheriff’s department.

She also created her own fake social media profiles to track Scales and collect evidence – information she’d eventually turn over to police. She captured screenshots of advertisements for homes rented by Scales. She scoured Google Earth and identified where Scales was living based on the photos.

Nick Penzenstadler

“I absolutely went down the rabbit hole. I got really deep in the weeds, almost obsessive,” Wilson said. “I can’t give you a number of hours, but I’ve been up taking screenshots of her social media at 2 in the morning.”

On social media, Scales seemed to be living her best life out in the open, bragging about her scams, and even posting a menu of fraud for potential clients. She offered to create pay stubs – $60 on regular paper or $100 on special paper – to sell apartment placements for $500, cable and internet accounts for $150.

In numerous Instagram and Facebook posts reviewed by USA TODAY, Scales flashes wads of cash and talks about her hustle.

At one point, Wilson decided to talk to Scales herself. She used a burner app on her cellphone to mask her identity.

“I told her we were coming for her and I wanted to hear her voice,” she said, adding that Scales abruptly hung up.

Provided by Zina Wilson

In July, Wilson took another approach. She spotted posts from Scales advertising merle English bulldogs – puppies born with an unusual mottled coat – for as much as $5,000. Wilson created another fake profile for “Shea Thompson” and inquired about buying one of the dogs. She hoped to persuade Las Vegas police to set up a sting.

Instead, she says, it took Webb and detectives until September to catch up with Scales. After setting up surveillance and gathering other evidence, they swooped in and arrested her. She was charged with 35 felony counts of identity theft, forgery, theft of credit and illegal possession of a Smith & Wesson .380 handgun.

Scales had lived in Houston before and was out of jail on bond for a similar scam with high-end cars. Police documents from Houston show she purchased a $52,424 Kia Stinger in 2021 using the identity – and credit rating – of yet another young Ohio woman. It’s unclear if she was selling the cars or just using them to promote an image on social media.

A week after her arrest in Las Vegas, Scales posted videos from a Caribbean cruise aboard the Symphony of the Seas, which she described as being shot “right before I went to jail … we had so much fun.”

Scales posted $50,000 bail through a bondsman in October and was released with a GPS ankle monitoring device, on house arrest.

Then, on Nov. 9, Scales cut off her ankle monitor and took off.

It wasn’t completely out of character. After failing to show up for court appearances in Texas, a warrant for her arrest had been issued in September in that state.

In Las Vegas, Judge Harmony Letizia revoked Scales’ bond and issued another warrant. A representative from Bob’s Bail Bonds in Las Vegas confirmed the firm had assigned a bail enforcement agent to track Scales down. The firm has 180 days from Nov. 9 – until May 8 – to find her before it will owe $50,000 to the court.

Attempts to reach Scales by phone and email were unsuccessful. All of her social media accounts were switched to private after USA TODAY began contacting her attorneys. Her attorney in Houston declined to answer questions for this report.

In Las Vegas, Scales had fired her public defender, and two subsequent private attorneys have withdrawn from her criminal case. Until she became a fugitive, she was due back in court in February for a preliminary hearing on the 35 felony counts. Now that hearing is in limbo.

For Wilson, the latest twist with Scales on the run is just another chapter in the two-year saga.

“I knew she’d do this. I even warned the detectives and court that she’d take off,” Wilson said. “It’s what she does.”

Weeks after celebrating Scales’ arrest, Wilson found herself back at her computer. She compiled her research files on associates, family and other information that might lead to Scales. She sent them off to Bob’s Bail Bonds.

The hunt was back on.

Nick Penzenstadler is a reporter on the USA TODAY investigations team. Contact him at [email protected] or @npenzenstadler, or on Signal at (720) 507-5273.

Source link