A measles outbreak in central Ohio that sickened 85 children has been declared over, officials at Columbus Public Health announced Sunday. None of the children died, but 36 were hospitalized.The outbreak of measles infections, which was first reported in early November, spread among children who were not fully vaccinated and was mostly driven by a lack of vaccination in the community. Among the 85 cases, all but five were ages 5 and younger.Measles cases in central Ohio emerged quickly in November and early December, but the number of new cases being identified appeared to slow during the winter holidays. Local health officials waited until no new cases were reported within 42 days -- or two incubation periods of the measles virus -- before declaring the outbreak over.Health officials fought the outbreak by "sounding the alarm," including being transparent about the state of the outbreak, informing the public about how easily the measles virus can spread and promoting the importance of getting young children vaccinated against the virus, said Dr. Mysheika Roberts, health commissioner for the city of Columbus, who led the outbreak response."In addition, we've had family members of individuals who have been infected with measles who have been very vocal and said they made a mistake -- they should have gotten their child vaccinated. And I think that has helped as well," she said.Experts recommend that children receive the measles, mumps and rubella -- known as the MMR -- vaccine in two doses: the first between 12 months and 15 months of age and a second between 4 and 6 years old. One dose is about 93% effective at preventing measles if a person comes into contact with the virus. Two doses are about 97% effective.In the United States, more than 90% of children have been vaccinated against measles, mumps and rubella by age 2, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.Measles was declared eliminated in the United States in 2000, and since then, most cases in the U.S. have emerged in communities with low rates of vaccination against the virus.Even if a disease is eliminated, outbreaks can still occur if an unvaccinated person travels to or from a country where the disease is still common, becomes infected and brings it back to the United States, introducing the virus into a community. That traveler can transmit measles to anyone who is unvaccinated."While we expect importations of measles cases into the United States to continue, the risk for measles for the majority of the population would still remain low," the CDC says on its website. "That is because most people in the United States are vaccinated against measles."How health officials stopped outbreak in its tracksWhen the outbreak began, the CDC sent a small team to Columbus to assist with tracking measles cases and pinpointing how the virus was spreading. Once a new case was identified, health officials worked quickly to determine who had been in contact with that person, whether the contacts were vaccinated against measles and, if not, whether they had been infected.About 90% of unvaccinated people who are exposed to measles will become infected, according to Columbus Public Health, and about 1 in 5 people in the U.S. who get measles will be hospitalized."Altogether, we had six CDC people helping us at one point in time on the ground, and that was very effective," Roberts said. "I think that really helped us slow the progression of this virus in our community."She added that the outbreak took Columbus Public Health officials off-guard."We've had low vaccination rates for MMR in our community for years, but we've never had a measles outbreak like we have now. So it did take us by surprise," Roberts said.There was not one single community or demographic of people within central Ohio that was at an increased risk of measles infections or had low vaccination rates. Rather, small pockets of communities where families decided not to get their children vaccinated were influenced by "false information that was distributed about the MMR vaccine being associated with autism," Roberts said, and that's what drove the outbreak.'One of the most contagious viruses that we've identified'Measles can spread through the air when an infected person coughs or sneezes or shares germs by touching objects or surfaces. Even after an infected person leaves a room, measles virus can live for up to two hours in the air.Symptoms can include fever, cough, runny nose, watery eyes and a rash of red spots. In rare cases, it may lead to pneumonia, encephalitis or death.Making sure children get the recommended MMR vaccinations as part of their routine childhood immunizations can help reduce their risk of measles, said Dr. Tanya Altmann, founder of Calabasas Pediatrics in California and author of "Baby & Toddler Basics," who is an adjunct clinical professor at Children's Hospital Los Angeles."Measles is one of the most contagious viruses that we've identified, and if one person has measles and there's somebody unvaccinated around them, there's a 90% chance they're going to get it," she said, adding that all of the children infected during the measles outbreak in Ohio were all not fully vaccinated."It really just takes one unvaccinated person to travel into a community, and they can have a measles outbreak if there isn't a high enough vaccination rate in that community," Altmann said.

A measles outbreak in central Ohio that sickened 85 children has been declared over, officials at Columbus Public Health announced Sunday. None of the children died, but 36 were hospitalized.

The outbreak of measles infections, which was first reported in early November, spread among children who were not fully vaccinated and was mostly driven by a lack of vaccination in the community. Among the 85 cases, all but five were ages 5 and younger.

Measles cases in central Ohio emerged quickly in November and early December, but the number of new cases being identified appeared to slow during the winter holidays. Local health officials waited until no new cases were reported within 42 days -- or two incubation periods of the measles virus -- before declaring the outbreak over.

Health officials fought the outbreak by "sounding the alarm," including being transparent about the state of the outbreak, informing the public about how easily the measles virus can spread and promoting the importance of getting young children vaccinated against the virus, said Dr. Mysheika Roberts, health commissioner for the city of Columbus, who led the outbreak response.

"In addition, we've had family members of individuals who have been infected with measles who have been very vocal and said they made a mistake -- they should have gotten their child vaccinated. And I think that has helped as well," she said.

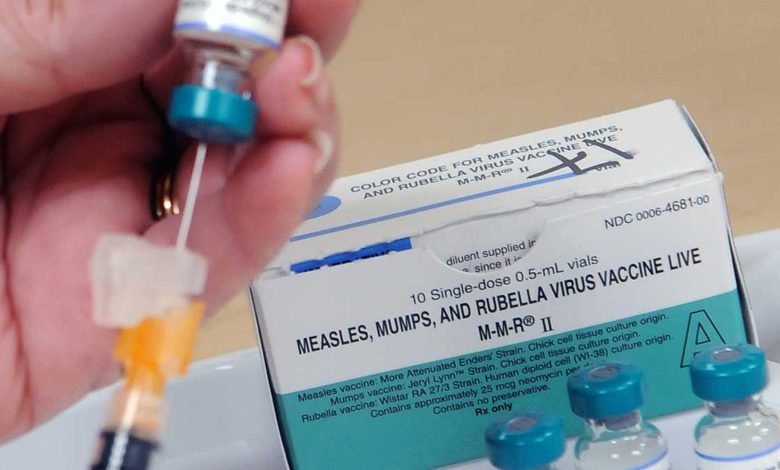

Experts recommend that children receive the measles, mumps and rubella -- known as the MMR -- vaccine in two doses: the first between 12 months and 15 months of age and a second between 4 and 6 years old. One dose is about 93% effective at preventing measles if a person comes into contact with the virus. Two doses are about 97% effective.

In the United States, more than 90% of children have been vaccinated against measles, mumps and rubella by age 2, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Measles was declared eliminated in the United States in 2000, and since then, most cases in the U.S. have emerged in communities with low rates of vaccination against the virus.

Even if a disease is eliminated, outbreaks can still occur if an unvaccinated person travels to or from a country where the disease is still common, becomes infected and brings it back to the United States, introducing the virus into a community. That traveler can transmit measles to anyone who is unvaccinated.

"While we expect importations of measles cases into the United States to continue, the risk for measles for the majority of the population would still remain low," the CDC says on its website. "That is because most people in the United States are vaccinated against measles."

How health officials stopped outbreak in its tracks

When the outbreak began, the CDC sent a small team to Columbus to assist with tracking measles cases and pinpointing how the virus was spreading. Once a new case was identified, health officials worked quickly to determine who had been in contact with that person, whether the contacts were vaccinated against measles and, if not, whether they had been infected.

About 90% of unvaccinated people who are exposed to measles will become infected, according to Columbus Public Health, and about 1 in 5 people in the U.S. who get measles will be hospitalized.

"Altogether, we had six CDC people helping us at one point in time on the ground, and that was very effective," Roberts said. "I think that really helped us slow the progression of this virus in our community."

She added that the outbreak took Columbus Public Health officials off-guard.

"We've had low vaccination rates for MMR in our community for years, but we've never had a measles outbreak like we have now. So it did take us by surprise," Roberts said.

There was not one single community or demographic of people within central Ohio that was at an increased risk of measles infections or had low vaccination rates. Rather, small pockets of communities where families decided not to get their children vaccinated were influenced by "false information that was distributed about the MMR vaccine being associated with autism," Roberts said, and that's what drove the outbreak.

'One of the most contagious viruses that we've identified'

Measles can spread through the air when an infected person coughs or sneezes or shares germs by touching objects or surfaces. Even after an infected person leaves a room, measles virus can live for up to two hours in the air.

Symptoms can include fever, cough, runny nose, watery eyes and a rash of red spots. In rare cases, it may lead to pneumonia, encephalitis or death.

Making sure children get the recommended MMR vaccinations as part of their routine childhood immunizations can help reduce their risk of measles, said Dr. Tanya Altmann, founder of Calabasas Pediatrics in California and author of "Baby & Toddler Basics," who is an adjunct clinical professor at Children's Hospital Los Angeles.

"Measles is one of the most contagious viruses that we've identified, and if one person has measles and there's somebody unvaccinated around them, there's a 90% chance they're going to get it," she said, adding that all of the children infected during the measles outbreak in Ohio were all not fully vaccinated.

"It really just takes one unvaccinated person to travel into a community, and they can have a measles outbreak if there isn't a high enough vaccination rate in that community," Altmann said.