SANTA FE, N.M. – On a late February morning, the undersecretary for thugs was in jeans and cowboy boots as he piloted the yellow Jeep Wrangler he's had for 10 years into still-sleepy downtown Santa Fe.

He parked by a low building amid the adobe and art galleries and pulled open a white office door with the unassuming label “W.B.R.” He settled into a leather chair and slid on his reading glasses. Soon he was on a conference call.

“How's our request to see those two Americans in China?” he asked his staff, avoiding some specifics because a USA TODAY journalist was in the room.

This tiny two-room office, dotted with keepsakes from a lifetime in politics and a power strip sprouting a tangle of phone chargers, was the headquarters of the Richardson Center for Global Engagement.

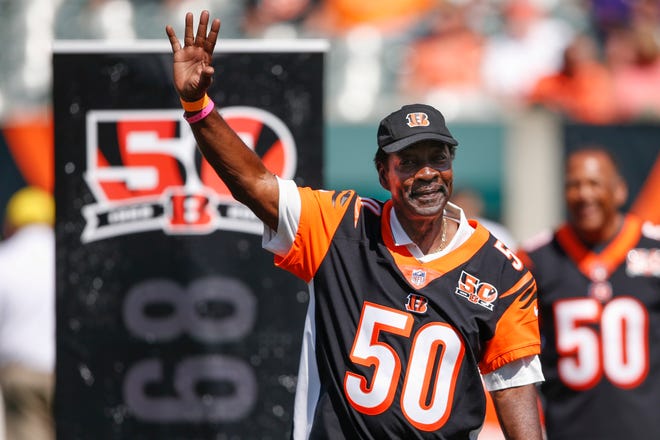

The man in the armchair was Bill Richardson, onetime presidential candidate, governor, secretary of energy, U.N. ambassador and congressman, the man who now spends much of his time as a private diplomat working on the crisis faced by more and more American families – finding ways to free their loved ones unjustly detained abroad.

“We've got hostage situations in Russia and Iran, China, Afghanistan,” he said, ticking off a few of the cases he and his small team were working.

They discussed Paul Whelan, the ex-Marine still being held in Russia. An American long imprisoned in Iran who’s growing despondent. A man jailed in Venezuela, whose home-state governor had asked Richardson to help.

There’s an Afghanistan case, but the State Department has asked them to pause on that one, he was told – the U.S. believes they have a promising approach. Richardson agreed, but said an anxious family would be pressing for progress. The list of countries and cases went on.

The voice on the speakerphone was Michael “Mickey” Bergman, director and second-in-command, a former Israeli Defense Forces member who directs the center's work. He was on the line from his home near Washington. Across the room was Richardson’s assistant.

Richardson furrowed his brow and slouched in the armchair, surrounded by the trappings of a life spent in interesting company: A guitar signed by the Eagles sits near a rug bearing the New Mexico state seal from his former job. His staff still calls him “the Governor,” a title he has not held in more than a decade. His reputation as the “undersecretary for thugs” for negotiating with despots was a moniker that one Clinton – Bill – helped give him years before he ran against the other one – Hillary – for the Democratic nomination for president.

At age 75, Richardson remains one of the country’s highest-profile private players working to free American prisoners and hostages in far-flung places – making headlines almost as often as he appears to chafe U.S. administrations with his efforts.

He has filled a whole book – its subtitle dubs him a "master negotiator" – with rollicking tales of high-stakes meetings with tribal leaders and tyrants. He talks with some affection about brokering deals with Fidel, Saddam, Hugo and "a Kim or two."

Lately, he had been on a good run. Over the preceding 15 months, Bergman says, 19 families in the Richardson Center’s portfolio have been reunited with their loved ones. In December, WNBA basketball star Brittney Griner walked free from a Russian prison in exchange for convicted Russian arms dealer Viktor Bout. While only the president can approve such high-profile swaps, Griner’s family also issued a public “special thank you” to Richardson for his role in pushing for her release.

Current and former U.S. officials, former captives and their families and representatives say Richardson’s work as a “fringe diplomat” can accelerate releases when others are unable to do so. His high profile can draw global attention to cases. His long list of contacts can open doors or get meetings. His negotiating tactics can flesh out prisoner-swap options for U.S. administrations to consider.

Yet for all of his storied exploits and the years he's devoted to hostage negotiations, elements of Richardson’s work remain as mysterious as the distant prison cells in some of his cases.

The State Department typically says little about how it handled a case, and rarely credits Richardson. Details of what exactly tipped a release – particularly when multiple parties are seeking an American’s return – often remain obscured. That’s fueled some grumbling that he takes outsized credit or could interfere with government efforts. The State Department declined an opportunity to comment on Richardson’s work.

Richardson shrugs off such criticism, saying he only wants to see Americans whose families seek his help come home.

Diane Foley – who created James W. Foley Legacy Foundation in part to improve the way the U.S. handles hostages after her son James was kidnapped and later killed by ISIS in Syria – thinks Richardson plays a valuable role.

She said the focus on occasional tensions can obscure a larger point.

“The Richardson Center tries very hard to work with our government. But at times, they're frustrating to the government too," she said. "But both sides are doing very good work ... and we need both government and nongovernment people working in this area."

Most agree, however, that wrongful detentions are a growing problem, highlighted by Russia’s arrest of Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich on espionage charges the U.S. says are false.

While hostage-taking historically was the act of terrorists or criminals, many Americans are also held in foreign states under what the U.S. considers unjust charges.

By one count, at least 54 U.S. citizens or permanent residents are now wrongfully detained or held as hostages in roughly 15 countries, and those are just the cases publicly disclosed – the real figure is thought to be far higher.

In the past decade, an average of 11 U.S. nationals were wrongfully detained each year, more than twice that from the decade prior, a 2022 report found.

Last year, President Joe Biden declared hostage-taking and wrongful detention a national emergency, adding new tools such as financial sanctions and visa bans. Currently, a Special Envoy for Hostage Affairs seeks to win the release of those designated as wrongfully detained by State Department. An FBI-led multiagency hostage recovery team also works to return Americans held hostage.

But some hostage advocates and family members still say their cases languish too long in bureaucracy. And that, in turn, has led many to seek additional help from private parties including Richardson.

On the recent day in his office, Richardson and his staff held a series of calls to discuss some of their cases. They weren’t all headline-making prisoners alleged to be held for political leverage. Some were under-the-radar Americans for whom they were trying to find a way out.

"All right, Mexico," Richardson said. "This is a case of a Navy veteran, jailed in Mexico for over a decade for a crime that he didn't commit. And we're working on that, without getting into names. Ana, what’s the latest?"

So far, said his assistant who was helping on the case, the responses are promising. The key to this case, Bergman chimed in, was to "applaud the Mexican judicial system for doing the right thing."

But they would have to move carefully.

13 years in prison in Mexico:

Calling in the governor

Just over one month later, Richardson was in Acapulco.

A sleek private jet, provided by insurance magnate Steve Menzies, whose global foundation also supports efforts to free U.S. citizens abroad, waited at the nearby airport.

Along with several members of his team, he was waiting for 46-year-old James Frisvold to be released from Mexican custody after years behind bars.

Richardson had recently completed a series of meetings with high-ranking officials in Mexico City and Guerrero, a state known for cartel violence.

He had first been asked to help by Jonathan Franks, a consultant for families of wrongfully detained Americans and a spokesman and strategist for the Bring Our Families Home campaign; Franks was working on behalf of Frisvold’s family, but he had hit a roadblock in his efforts to accelerate long-stalled criminal court proceedings.

"I can't talk to high-level Mexican officials. They aren't interested in receiving me,” he said.

To be sure, it wasn’t the sort of case the Richardson Center typically worked on. Most of its cases typically involve prisoners and hostages held by hostile regimes or criminal organizations. It can involve convincing leaders it is in their interest to release prisoners, fleshing out a potential exchange or working through foreign court systems.

In this case, Frisvold, a Navy veteran living near Sacramento, had been jailed since traveling to Acapulco in 2010 with a golfing friend from home, Jerald Kenneth Schultz, and Shultz's Russian-born wife, Natalya Sidorova.

While there, Schultz’s wife was attacked and stabbed by an assailant in a hotel hallway. Surveillance video footage viewed by USA TODAY shows Shultz stepping back to watch the attack and talking with the assailant before getting help.

After Schultz was arrested, he identified Frisvold as the killer, Franks said. Both men were charged in connection with the murder.

Schultz died in 2015, according to court documents. But Frisvold remained stuck in prison, claiming innocence in an apparent criminal plot he didn’t understand.

The prison was “hell,” he said. His family hired attorneys on his behalf, he said, but delays stretched into years. “The translator wouldn't show up. And next thing you know, another year goes by,” he said.

In 2019, a court threw out a previous conviction, Franks said. Court records show Mexican forensic analysts concluded Frisvold was not the man in the video, and that his fingerprints weren't on the weapon, but delays in a retrial dragged on.

Franks, convinced Frisvold deserved to be freed after scouring thousands of pages of court records and other evidence, got the issue referred to a high court and an investigation launched. But he decided he needed Richardson’s high profile to bring the case to a conclusion.

On March 29, after a flurry of work and meetings, a Mexican judge acquitted Frisvold of the homicide charge, according to court documents viewed by USA TODAY.

Franks, who said his client’s plight was left to languish by both U.S. officials and Mexican courts, credits Richardson with pushing the case over the finish line.

A State Department spokesperson told USA TODAY the government was “aware” of Frisvold’s release but that, “due to privacy considerations, we have no further comment at this time."

On the day he was released, Frisvold said, he was transferred from prison to be processed at an immigration detention center near the tourist center of Acapulco. From there, he met Richardson and his team, including Bergman, at a hotel.

“I fought for my innocence for 13 years,”’ he told USA TODAY. “I'm just grateful to be heading home.”

Richardson joked with him to put him at ease, he recalled, offering him drinks and taking photos. They planned to whisk him to California on the private jet. But there was a problem. Frisvold, after sitting in jail for more than a decade, didn’t have a valid passport.

Richardson’s presence helped there, too.

“Gov was able to interface at a very high level with the embassy,” Franks said, “and we were able to get a passport waiver.”

A 1994 surprise in North Korea:

Becoming the ‘fringe diplomat’

The job Richardson has carved out freeing Americans began by accident.

It was 1994, Richardson was deep into a career as a U.S. Representative from Santa Fe, and he was on a Congressional trip to North Korea to discuss nuclear issues.

While he was there, a U.S. Army helicopter was shot down after it veered off course in the demilitarized zone that separates North from South Korea. One American died and the other was taken into North Korean custody.

“I remember Secretary of State Warren Christopher calling me and saying, ‘Don't leave, please, until you get the two pilots out.’”

The visit stretched into five days of tense negotiations pressing for the return of one soldier’s remains and freedom for the other, which he eventually won.

Similar exploits over the next two years and beyond built his reputation as a go-to negotiator for wresting prisoners from dictators, terrorists and regimes hostile to the United States.

He traveled to Baghdad for a one-on-one with Saddam Hussein to secure the release of two Americans who had wandered over the Kuwaiti border.

Saddam Hussein at one point slammed his fist on the table and walked out, after Richardson inadvertently crossed his legs, creating a cultural offense by showing the bottom of his shoes.

Richardson said he decided not to apologize or to leave, a show of resolve that he credits with eventually salvaging his mission.

In 1996, Sudanese rebels had taken two Red Cross workers and a New Mexico constituent hostage. They were held in a reed hut on a $2.5 million ransom. Richardson flew in an old cargo plane to meet the rebel leader.

After sharing chunks of goat meat as boys with AK-47s stood nearby, he talked the leader into accepting rice, radios, four Jeeps, a health survey and a promise to work on resolving conflict in the area, according to reports at the time and Richardson's own account of the episode.

Upon Richardson's return, the Washington Post declared, “The once low-profile lawmaker is now called the Clark Kent of Capitol Hill.”

Then-national security adviser Anthony Lake and others quoted in the story said Richardson’s personal touch, along with his ability to operate as a “friend of the administration, but not part of the administration," made him effective.

Soon, he would be part of the administration.

Shortly after Richardson returned from Sudan, President Clinton appointed him as Ambassador to the United Nations, joking in the Rose Garden that he’d just returned from a rebel chieftain's hut in Sudan.

Later, Richardson recalled how Secretary of State Madeleine Albright told him things had now changed: “You can't be an outlaw ambassador. You’re in the administration.”

“President Clinton used to say Bill knew all the thugs,” Richardson’s wife, Barbara, to whom he has been married for five decades, recalled. “He had a knack for it. And I think he liked the adventure of it. And it just sort of grew from there.”

From the post at the United Nations, the Richardsons lived in New York while meeting key contacts from around the globe that would serve him later. His former U.N. counterpart from Russia was at the time a man named Sergey Viktorovich Lavrov. Today, Lavrov is Russia’s foreign minister.

Richardson went on to serve as energy secretary and two terms as governor of New Mexico, and to make a short-lived run at the presidency. He still was called on to broker releases with difficult leaders and countries – bringing both success, shortfalls and heartbreaking ends.

In 2006, he rescued Paul Salopek, a Chicago Tribune reporter, from Sudan. In 2013, he tried but fell short of bringing back imprisoned missionary Kenneth Bae from North Korea. A few years later, he helped get Otto Warmbier, an Ohio college student, home – but Warmbier, who had become comatose during captivity, died soon after.

Richardson in 2011 founded his nonprofit to do that work without taking any money from the desperate families who sought his help. Donations – which records show have fluctuated but which Bergman said in 2022 was roughly a million dollars – come largely from wealthy supporters and several grantors. Richardson takes no salary, but those fund a small staff that includes his assistant and several consultants including former U.S. ambassador and career diplomat Cameron Hume and Bergman. Richardson first heard of Bergman through his international humanitarian work in Sudan, which led to their first foreign mission.

"I get a phone call one morning and this rough-sounding voice comes on the line and says: 'This is Gov. Richardson. I need you to pack your stuff and get your ass to Santa Fe. You're flying with me to Khartoum,’” Bergman recalled.

Bergman now works on everything from bookkeeping and fundraising to logistics and negotiation strategy. He said he and Richardson – who he described as a charismatic negotiator who can charm, bluff and bully – play off each other for different needs depending on the case.

“He might be the one threatening and bullying and burning a bridge, and I'm going to be the one kind of like, ‘Hey, guys, you know, we can still fix it,’” he said.

The Richardson Center isn't the only private group that seeks to negotiate the return of captives at the request of families, said Foley, whose foundation maintains a list of groups or people who are credible and ethical. But most work confidentially and stay "under the radar," she said, while Richardson Center is among the most public with whom they work.

Over the years, Richardson found success as well as controversy in the same gray area he had staked out early on: as a friend of the administration, not part of the administration.

They choose cases where they think they make a difference, Richardson said. Currently, Richardson has let the family of Gershkovich know that the Richardson Center’s “door is open and they can reach out if they want to, but we’re not pushing,” according to Bergman.

Once he’s working a case, that means keeping in touch with contacts inside and outside the government. This can mean officials from the U.S. State Department, National Security Council and the Special Presidential Envoy for Hostage Affairs. Outside government, this can mean a revolving cast of former diplomats, intelligence and law enforcement officials. U.S. officials who have worked closely with Richardson declined an opportunity to comment on his efforts.

But it can also mean pressing on alone when needed.

“We try to coordinate with the U.S. government when it's helpful, but we don't work for the government,” Richardson said. “We consult with them. Our responsibility is to the families.”

Foley said Richardson's brand of private diplomacy has often been "very effective, just through personal relationships.”

A cold January on the Russian border:

Old friends in high places

Under lead-gray skies and freezing January winds along the Polish border, Bergman was in his car on a reconnaissance trip.

It was January 2023, and he and Richardson were hoping to retrieve Taylor Dudley. The 35-year-old Lansing, Michigan, man had been imprisoned by Russia nine months earlier after apparently wandering into the country while backpacking in Europe.

He was set to be released from jail in Kaliningrad, a small patch of Russian territory surrounded by Poland and Lithuania and a small strip of Baltic Sea coastline, and Bergman was checking the entry points in case the Russian dropoff plan suddenly changed.

Dudley was taken prisoner in April 2022, though he hadn’t been designated by the U.S. as having been wrongfully detained.

His family soon appealed to the Richardson Center, who brought in Franks, the crisis consultant, who believed the U.S. wasn’t doing enough on the case.

Richardson already had his hands full with cases connected to Russia that year, seeking to speed up a deal in several that had grabbed media attention.

There was Whelan, the Michigan corporate security executive deemed wrongfully detained in 2018 on suspicion of spying and later sentenced to 16 years. There was Reed, detained in 2019 after an alleged drunken assault on two Moscow police officers. And there was Griner, arrested in 2022 after police said they found cannabis oil in her luggage.

Richardson traveled to Russia at least twice in 2022, Hume said, to have dinner meetings at Moscow restaurants. At those meetings: Lavrov, his long-ago counterpart at the U.N. – now the top Russian diplomat charged with explaining the decisions of his boss Vladimir Putin. Those moves, from the invasion of Ukraine to support for dictators, have turned Moscow into a pariah in much of the world.

The Richardson Center, in addition to working their array of contacts, was also advising Griner's family and supporters, said her agent, Lindsay Kagawa Colas. "We did not make any major moves without consulting them," Colas said. Griner's wife or representatives "spoke with Mickey on almost a daily basis."

That same year saw tensions bubble to the surface with some administration officials – stoking a narrative that has clung to Richardson for years.

In July of that year, Politico reported that Richardson often sparked eye rolls, citing anonymous sources to report that "many within the White House and State Department feel that while the governor cares about the families, he also uses detainees as a way to maintain relevance in international affairs, and takes credit for efforts where he played little role.” (Bergman said that "Sometimes, the extent of our involvement is not known or understood by every government official.")

Then in September, as the work to secure Griner’s release gathered pace, State Department spokesman Ned Price warned such private intervention could foil government efforts.

"We want to make sure that any outside effort is fully and transparently coordinated with us," he said. "In this case, we believe that any efforts that fall outside of that officially designated channel have the potential to complicate what is already an extraordinarily complicated challenge that we face."

Richardson, no stranger to such friction, was not dismayed.

He kept working his contacts in Russia.

“The visits to Russia, especially the one in September, were highly critical for the Dudley case,” said Bergman.

Another key contact was Ara Abramyan, an Armenian businessman and Russian-speaking philanthropist and president of the Union of Armenians of Russia, an organization that represents the interests of one of Russia's largest ethnic minority groups.

Abramyan had the ear of senior officials in the Kremlin. He had already worked behind the scenes to help free Reed, who was traded in late April 2022 for Konstantin Yaroshenko, a Russian smuggler convicted of conspiring to import cocaine.

Reed’s father, Joey Reed, said he believes that release was aided by a White House meeting with President Joe Biden. But he also credits Richardson for adding to the push for both sides to come to an agreement.

“It all depends upon the president, but had (Richardson) not gone and broke the ice and put deals on the table? I don't know how far the bureaucracy would have gone,” said Joey Reed.

Abramyan would also play a role in freeing Griner, who was traded eight months later for Bout, the notorious Russian arms dealer. Abramyan could not be reached for comment for this story.

When it came to Dudley – whose release was not a trade but a humanitarian appeal – the Richardson Center said in a statement that it went to work “discreetly,” traveling to Moscow and Kaliningrad “multiple times, liaising with our Russian counterparts and conduits.”

Whatever the strategy’s fine print, it worked.

Just a few weeks after Griner’s return, Richardson got word Dudley would be released – deported, technically – on Jan. 12. He and Bergman traveled to the Polish border with Dudley’s mother.

"We knew which crossing the Russians were going to bring him over through," said Bergman. "But we had to be prepared in case they changed their mind, in case they decided last-minute to use a different crossing. So we drove to all of them so we knew what we were dealing with."

Finally, their two rental vans waited near the Russia-Poland Bagrationovsk-Bezledy border crossing.

Richardson, Bergman and an American security contractor were in the front van.

Franks, Taylor's mother, Shelley VanConant, a doctor, and a second American security contractor followed closely.

Both vehicles pulled up close to the Russian checkpoint.

The Russian authorities had deposited Dudley on a charter bus that was also carrying Russians who were crossing into Poland to go shopping.

Dudley and his mother embraced tightly after months of fear and anxiety.

"He looked a little dazed," said Franks, explaining it’s not an uncommon reaction. “Part of them is like, 'OK, is this real? Am I actually out?”

A secret deal in Myanmar:

‘Who is this guy?’

In late 2021, Richardson found himself in Myanmar’s capital city.

He sat on a chair across from the leader of a military junta globally condemned for a coup, a deadly crackdown on government protests and persecution of the Rohingya minority.

The former governor was ostensibly in Naypyitaw to discuss COVID-19 and humanitarian aid. But his eyes were on an American journalist named Danny Fenster.

U.S. officials, however, had specifically asked Richardson not to bring him up.

Fenster, 38, spent six months in a Myanmar prison after he was detained over false claims he violated the country's immigration and terrorism laws. He’d become a global cause celebre.

According to Bergman, State Department officials believed they were making progress on Fenster’s release and had asked Richardson to postpone the trip to Myanmar. They wanted him to sit tight and let the process unfold, fearing Richardson would set back their efforts.

But after a few weeks of stalling, Richardson concluded he couldn’t further delay a difficult-to-get invitation from senior Myanmar officials to talk about vaccines and the country’s humanitarian needs – topics he viewed as a “Trojan horse” that could give him a window to bring up Fenster, Bergman said.

Bergman informed the State Department the trip was going ahead. He told Fenster’s family that U.S. officials asked Richardson not to raise Fenster’s name while he was there.

He heard what they had to say, but made no such commitment either way.

Richardson was familiar with Myanmar, previously known as Burma, through past work with former leader Aung San Suu Kyi dating to the 1990s. Since then, Suu Kyi had been deposed, military leader Min Aung Hlaing was in charge, and now Fenster was in jail.

"We’d been working on it for about a year, quietly, with the Burmese,” Richardson said. “But with the Burmese, it's the leader, the general, who decides. Everything else doesn't matter.”

But how? He wasn’t asking for a prisoner exchange.

Min Aung Hlaing was a man used to crushing dissent through violence, covert interrogations and fear. But he was also shy. This appeared to be a potential opening.

Richardson asked to talk to him alone.

He flattered Min Aung Hlaing by telling him he possessed a "quiet leadership," one all the more powerful because it deliberately avoided melodrama and bluster. The two men started talking about their families. A connection was being formed.

Richardson decided he was on a roll. He pressed further.

“There’s this American,” Richardson recalled saying, appealing for Fenster's release by telling the general it could help his poor image in the U.S. “It would be good for the American people, they'd like it because (Fenster’s) been in the news a lot. Let him go. Let me take him back.”

The general seemed to agree to Richardson’s proposal. But he wouldn’t do it right away.

“I'm going to give him to you,” Myanmar’s leader said, as Bergman would later recall in an interview for a podcast. “And I'm going to do it here. But it's going to take me time.” The governor looked at him, laughed and he said, “Well, I have my plane here for two more days.”

It was going to take more time than that. Two weeks, maybe a month.

Richardson reluctantly agreed he would come back for Fenster.

He also asked for the release of a lower-profile person, a local imprisoned activist who had worked for the Richardson Center in Myanmar. The general agreed. She was delivered to their hotel the next day.

But when Richardson left Mymanar, his entire discussion about Fenster with the general was still a secret, Bergman says.

And because Richardson returned home without Fenster, he took a barrage of public and private criticism for giving the junta credibility. In fact, about a week later, Fenster was sentenced to 11 years of hard labor in prison.

“Did zilch, zero nothing for human rights in #Myanmar while giving a propaganda win to #Burma’s nasty, rights abusing military junta. Pathetic,” Phil Robertson, Human Rights Watch deputy Asia director, tweeted at the time. Robertson declined to comment for this story.

But the draconian sentence had all been part of a familiar process, a performance, Bergman says now, allowing the general to later pardon Fenster.

Not long after, Richardson was called back to Myanmar and Fenster was being delivered to the airport. Richardson and Bergman were there with an airplane to pick him up.

Fenster’s clothes were a mess and he had on flip-flops that were falling apart. He’d been surviving on rice and water for six months. On the plane ride home with Richardson and Bergman, he devoured a shrimp cocktail, beer and coffee.

Despite the earlier criticism, Richardson’s gamble had paid off.

"I knew I had an opportunity, and we got him out," he said.

Afterward, Roger Carstens, the Biden administration’s special envoy for hostage affairs, thanked Richardson for securing Fenster’s release.

“I just can't get upset when the governor actually brings him home. We have no pride of authorship. Whoever can come up with a plan and get someone out, we're down for the win,” he told 60 Minutes.

A White House spokesperson later told Rolling Stone magazine that it was, in fact, the U.S. government that secured Fenster’s release.

And while Fenster believes Richardson's intervention played a big role in his release, he doesn't want to discount the possibility that Myanmar's authorities, who he described as "incompetent" and perhaps not fully aware of what they were doing when they detained an American journalist, may have been looking for an excuse to get rid of him.

"They had a lot of people asking them to let me go and maybe they were just like, 'Well, here's somebody to give him to,'" said Fenster. He stressed that he remains hugely appreciative to Bergman and Richardson for advocating on his behalf.

Some hostage advocates, such as Foley, say the reality is that the goal of returning captive Americans often benefits from both private and public efforts. That’s been true in the most recent case of the detained Wall Street Journal reporter.

“We’re trying to bring all elements of this government. … Trying to partner with members on Capitol Hill, members of the media, frankly, third-party intermediaries, nonprofits, NGOs and also the family to bring Evan home,” Carstens, the U.S. hostage envoy, said in a recent interview with NBC’s “Today” show.

A top Russian diplomat has said that Russia might be willing to discuss a prisoner swap. “We have a working channel that was used in the past to achieve concrete agreements," Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov told a state news agency, according to the Associated Press. But Ryabkov said any discussion with the U.S. would happen only after Gershkovich's trial.

In Fenster's case, he discovered that his sentencing was a step toward freedom.

In the podcast about the Fenster case, Bergman describes the moment Myanmar officials handed Fenster over to him at the airport.

"He's like, 'Mickey, I need to ask you a question, I'm sorry, I just – who is this guy?'"

Bergman blinked, asking him, “'You mean, Gov. Richardson?'"

“That's what I thought!” Fenster replied. “But I was told last week that he's the reason I got the sentencing!'"

Bergman, recounting the story, seems to smile.

“Well, you were told a lot of things that were not accurate,” he told Fenster. “But it doesn't matter. … We're going home."

Back home in Santa Fe:

The governor gets things done

Back in his office in Santa Fe, Richardson finished strategizing on detained Americans and launched into other projects his nonprofit was working on.

He got an update on humanitarian programs for displaced Rohingya, then met to talk about a Navajo Nation aid project.

He was also planning for an interview with a Russian state media reporter, in which he hoped to telegraph a message welcoming prisoner negotiations. Then he set aside his cases for a break to visit his favorite lunch joint in his adopted home town.

Over his three decades of high-wire negotiations and secretive meetings in nations with little love for the United States, it’s here that Richardson returns home to decompress.

Richardson moved here in 1978, after a childhood that prepared him for the work he does now.

He grew up immersed in a bilingual home and school in Mexico City, the son of a U.S. Citibank executive, which impressed on him the importance of dialogue, language and diplomacy, before attending boarding school in Massachusetts as a young teen.

Richardson wanted to play baseball for a living. Instead, he studied politics and international affairs before working in positions including under Henry Kissinger’s State Department.

All these years later, much has changed about the work and the world he travels in.

But there are constants: He needs to find a key that will open a door for desperate families, and captives.

On the day in late February, Richardson said he was pained that he wasn’t able to free Whelan along with Griner, who he initially thought would be part of the same prisoner swap.

He was also trying to find an opening for prisoners in Iran, including Emad Shargi, an American businessman who was first arrested in Iran in 2015 and is held at Tehran’s Evin Prison.

His sister, Neda Sharghi, who spells her last name differently, said she’s frustrated with the lack of progress by the U.S. government. She’s been unable to meet with President Biden in hopes of making it a bigger priority.

"I hear that it's complicated. And I hear that this is their top priority. But that's it," said Sharghi, who is part of the Bring Our Families Home campaign.

Families of hostages have become increasingly vocal and organized since Foley and other captives were killed in 2014 and 2015, an episode that partly led to a hostage policy overhaul under the Obama administration that created the hostage envoy and recovery team.

Before then, the federal government insisted on secrecy in such cases, but that secrecy meant both the public and the hostages’ families had no way to know what was being done. “I tried to work with the U.S. government when Jim was captured,” Diane Foley said in 2019. “It was terrible at the time. It was nobody's job.” (Former President Donald Trump broke with decades of U.S. hostage policy in his own way, using Twitter and photo opportunities to inject himself into the process and highlight his self-professed skills as a deal-maker.)

She says the U.S. approach still can be too inefficient, slow and opaque. Neda Sharghi, who turned to Richardson for help, said she knows he can’t bargain on behalf of the government. But she said the center has provided key guidance for the family as they push publicly for a deal leading to his release.

“I always say go public. The government says no, don’t, because then you raise the stakes,” Richardson says. “It's better to have the press and pundits and Congress advocating for you.”

Sharghi said keeping a case in the public eye can be critical.

"What the Richardson center always reminds everyone is that, at the end of the day, these are human beings that are being used, and it's our responsibility to do whatever is needed to bring them home," she said.

Soon Richardson was bellying up to the bar to order a tamale and posole next to a group of friends and lunch regulars.

“Hey Gov,” several said as they walked in.

The down-to-earth affability that aided him as a politician and negotiator was on full display. He shook hands, traded banter and tried to stump a friend in a cowboy hat and turquoise ring, who says he once worked for Elvis, with baseball and music trivia.

At one point, a man came up behind him to ask him for help with a family immigration issue.

Richardson doesn’t get involved in many issues in New Mexico. But it’s not surprising if he’s seen as a problem-solver, the undersecretary who might just get it done.

He leaned his head in.

“What do we need to do?”

Contributing: Rick Jervis, USA TODAY.