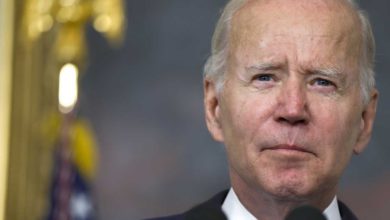

WASHINGTON — Former Sen. Bob Dole, a Kansas lawmaker and decorated World War II veteran who never realized his ambitions to win the presidency but left an indelible mark on the nation’s capital and history, died Sunday. He was 98.

Dole died in his sleep, according to an announcement from the Elizabeth Dole Foundation.

For all his accomplishments, Dole wanted to be remembered for his service – particularly as a soldier who lost the use of his right arm on the battlefield in Italy. He described to Fox News in May 2013 how he wanted to be remembered: "Veteran who gave his most for his country."

As a politician, Dole was a major force in the Republican Party for three decades. That service began in 1971, when he was its national chairman, and culminated in 1996, as the GOP presidential nominee in an election lost to Democrat Bill Clinton. Dole holds the record as the Senate’s longest-serving Republican leader, a post he held for nearly 11 years.

Late in life, Dole was hospitalized from time to time at Walter Reed National Military Center with a variety of ailments. In February, Dole announced he had lung cancer.

More:At 98 and facing cancer, Bob Dole reckons with legacy of Trump and ponders future of GOP

He has maintained a low public profile in recent years, although Dole was the lone former presidential nominee to attend the 2016 Republican National Convention.

In one of his last public pronouncements, the former standard bearer criticized his party for a lack of ideas and a tilt so conservative that icons such as Ronald Reagan – and himself – could not make it in today’s Republican Party.

“I think they ought to put a sign on the national committee doors that says ‘closed for repairs’ until New Year’s Day next year and spend that time going over ideas and positive agendas,” Dole said.

Dole’s political career spanned what came to be called “the American century,” and he played a role in many of its pivotal moments. He fought – and lost the use of his right arm and nearly died – in World War II, helped pass landmark civil rights legislation in the 1960s and later spearheaded a bill to make Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday a national holiday.

Dole steered his party through the Watergate crisis of the 1970s, and pushed to expand opportunities for the disabled and improve nutrition for the disadvantaged during 27 years as a senator. He played a key role in a 1983 compromise that saved Social Security from insolvency.

“He was one of the greatest of the greatest generation,” said Whit Ayres, a longtime Republican consultant.

After leaving public life, Dole helped raise more than $197 million for a memorial to his fellow World War II veterans on the National Mall. He also co-chaired a presidential commission in 2007 that investigated substandard conditions at Walter Reed Army Medical Center. He spent 18 months working with other former Senate majority leaders — Democrats George Mitchell and Tom Daschle and fellow Republican Howard Baker — on a bipartisan list of recommendations for improving the nation’s health care system that was issued July 2009.

In poignant scenes he visited the U.S. Capitol to honor fellow politicians and World War II veterans.

In December 2012, he said goodbye to fellow veteran, Senate colleague and lifelong friend Daniel Inouye, a Democrat. With some help, he lifted himself out of his wheelchair to walk across the Rotunda to salute the casket of Inouye, a Medal of Honor winner who represented Hawaii in the Senate and House for 50 years. Dole and Inouye, who also lost an arm in battle, became friends recuperating at the same Army hospital.

And in 2018, Dole rose to honor former President George H.W. Bush. Dole, then 95, relied on an aide to help him stand on the floor of the Capitol rotunda before offering his gesture beside the casket of Bush, his onetime rival in the 1988 Republican presidential primary.

Bush's spokesman, Jim McGrath, described the salute as "a last, powerful gesture of respect from one member of the Greatest Generation, @SenatorDole, to another."

Despite his party affiliation and advancing age, Dole was a politician who could change with the times. He appointed the Senate’s first female chief of staff and the first woman to serve as secretary of the Senate. In 1999, Dole made headlines by openly discussing male impotence problems in ads for Viagra.

Dole and his second wife, Elizabeth, made one of Washington’s most glamorous power couples. A Harvard-educated lawyer, she served as secretary of transportation in Ronald Reagan’s administration, secretary of Labor under George H.W. Bush and president of the American Red Cross. Dole campaigned for his wife when she successfully ran for a Senate seat from her native North Carolina, a post she held for one term, from 2003 through 2009.

“I regret that I have but one wife to give for my country,” Dole quipped.

World War II injury nearly killed Dole

Humor was one of Dole’s trademarks, as was his habit of referring himself in the third person. Joking about the bureaucracy he endured as an Army infantryman, he liked to say, “I was a boy from the plains of Kansas, so they sent me to the Alps.”

In Italy, Dole was gravely wounded while trying to rescue another soldier. He spent 39 months in hospitals and endured eight surgeries. Twice he had life-threatening infections. At one point, his temperature climbed to nearly 109 degrees. He never regained the use of his right arm. Throughout his political career, Dole made a habit of carrying a pen in his right hand to prevent others from trying to shake it.

Dole had been a promising athlete who was planning to go out for football, basketball and track when the war interrupted his college career. After his injury, he channeled his competitive energies into politics.

From partisan to dealmaker

His ability to adapt to changing circumstances would come to the fore again when Dole, a sharp-edged partisan at the outset of his Washington career, matured into one of the town’s consummate dealmakers, who had high-powered admirers in both parties.

Dole entered Congress in 1961, a few weeks before another Kansan – President Dwight Eisenhower – left office. Dole won a U.S. House seat after a tough Republican primary fight against Keith Sebelius, a state senator. Sebelius later succeeded Dole in the U.S. House and became his friend. Sebelius’ daughter-in-law, Kathleen, was elected governor of Kansas as a Democrat in 2003, then secretary of Health and Human Services under President Barack Obama.

Elected to the Senate in 1968, the same year Richard Nixon won the White House, Dole first drew the attention of party leaders for his aggressive partisanship and staunch defense of the president’s Vietnam strategy.

Sen. William Saxbe of Ohio, a less conservative Republican, described Dole in The New York Times as “a hatchet man.” More admiringly, Sen. Barry Goldwater, R-Ariz., said the party finally had in Dole someone who “could grab ’em by the hair and haul them down the aisle.”

As Gerald Ford’s vice presidential running mate in 1976, Dole famously described American battlefield deaths of the 20th century as casualties of “Democrat wars.”

Nor was Dole’s brusqueness confined to the political arena. “I want out,” is how he informed his first wife, Phyllis, of his plans to file for a divorce in 1971. The couple had a daughter, Robin, who began campaigning for her father as a toddler, wearing “I’m for my Daddy” pins, and continued to do so through his 1996 run for the White House.

In 1988, during the second of his three tries for the presidency, he physically confronted his chief rival, then-Vice President George H.W. Bush, on the floor of the Senate. Dole told a TV interviewer that Bush should “stop lying about my record.” Dole made an effort to soften his image after his loss in that campaign.

As he took on more leadership responsibility in the Senate, a body whose rules practically require bipartisan cooperation to move legislation, Dole began to cultivate allies across political and ideological lines.

He worked with Democrat Edward Kennedy to enact the Americans with Disabilities Act and Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan, D-N.Y., to save Social Security from bankruptcy. Years before his death in 2012, George McGovern of South Dakota – the Democratic Party’s presidential nominee in 1972, when Dole chaired the GOP – became a partner in efforts to expand the food stamp program.

In late 1995, Dole angered some members of his own party and put his own political hopes at risk by helping President Bill Clinton — the man Dole hoped to unseat the following year — win the Republican-controlled Senate’s support for U.S. intervention in Bosnia. Dole’s selfless action convinced fellow Republican Sen. John McCain, who was heading up Sen. Phil Gramm’s presidential campaign at the time, to declare in his memoir that he “had backed the wrong man for president.”

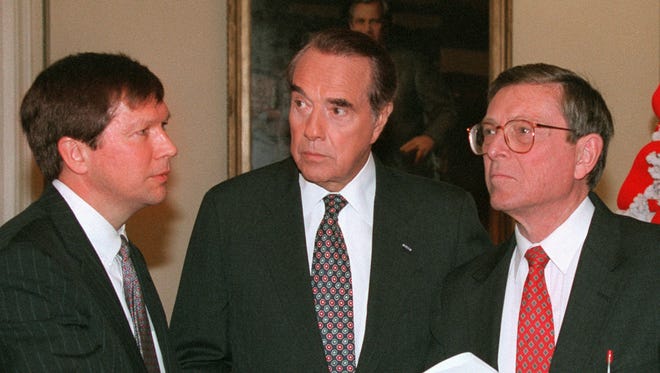

When Dole retired from the Senate in 1996. to devote himself full-time to his third – and last – presidential campaign, the onetime hatchet man had become so well-respected that Democrats sent the GOP candidate off with bouquets for his kindness and leadership. “He leaves this place with the gratitude of us all,” said the Senate’s Democratic leader at the time, Tom Daschle of South Dakota.

Dole’s colleagues passed a resolution naming one of Dole’s favorite spots — an ornate porch off the GOP leader’s office with a spectacular view of the National Mall — the “Robert J. Dole Balcony.” That’s a slightly more formal version of “the Dole Beach,” the nickname it got when Dole used it to collar recalcitrant legislators for long chats there.

“His key was patience, absolute patience,” says former senator Alan Simpson, a Wyoming Republican who served as Dole’s deputy leader. “Dole was just a guy who wanted to make the trains run. He had an innate sense of where the trickery was going on.”

Final run at White House

Dole gave the 1996 White House race his best shot, recruiting Jack Kemp, a favorite of GOP conservatives, as his running mate even though the two men had feuded over supply-side economic theories (Kemp bought them; Dole didn’t). In Clinton, Dole had a young, incumbent opponent presiding over a booming economy in peacetime.

Scott Reed, who managed the GOP presidential campaign, said Dole mounted an all-out, 96-hour campaign marathon in the closing hours of the race not for his own sake — “We knew we were going to lose” — but to help other Republican candidates. “That was classic Dole,” Reed said.

Reed said he regrets advising Dole to rein in his acerbic wit. “That was a mistake,” he said, “because people didn’t see the real Bob Dole.”

Once the campaign was over, Dole volunteered to help the man who beat him, serving as Clinton’s envoy in Bosnia and throwing himself into the effort to make the World War II memorial a reality. For Dole, extending a hand to a political opponent had become the quintessence of patriotism.

At the World War II memorial’s 2004 dedication, Dole called the monument of stately granite columns, graceful bronze wreathes and placid fountains a tribute to a “people who in the crucible of war forged a unity that became our ultimate weapon.”

He made regular visits to the memorial, without fanfare, to greet other veterans. “It’s like he had discovered late in life one of the most important things,” says Sen. Dan Coats, an Indiana Republican who served with Dole in the Senate and later shared a law office with him.

In retirement, Dole continued lending his name and energies to one of his other favorite causes: opening doors for the disabled. In a 2005 interview with Caring magazine, Dole called passage of the 199 Americans with Disabilities Act his proudest achievement as a senator.

Asked once how he’d like to be remembered, he said, “As somebody who had a sense of humor, who got along well with people and who kept his word.”

Contributing: Catalina Camia