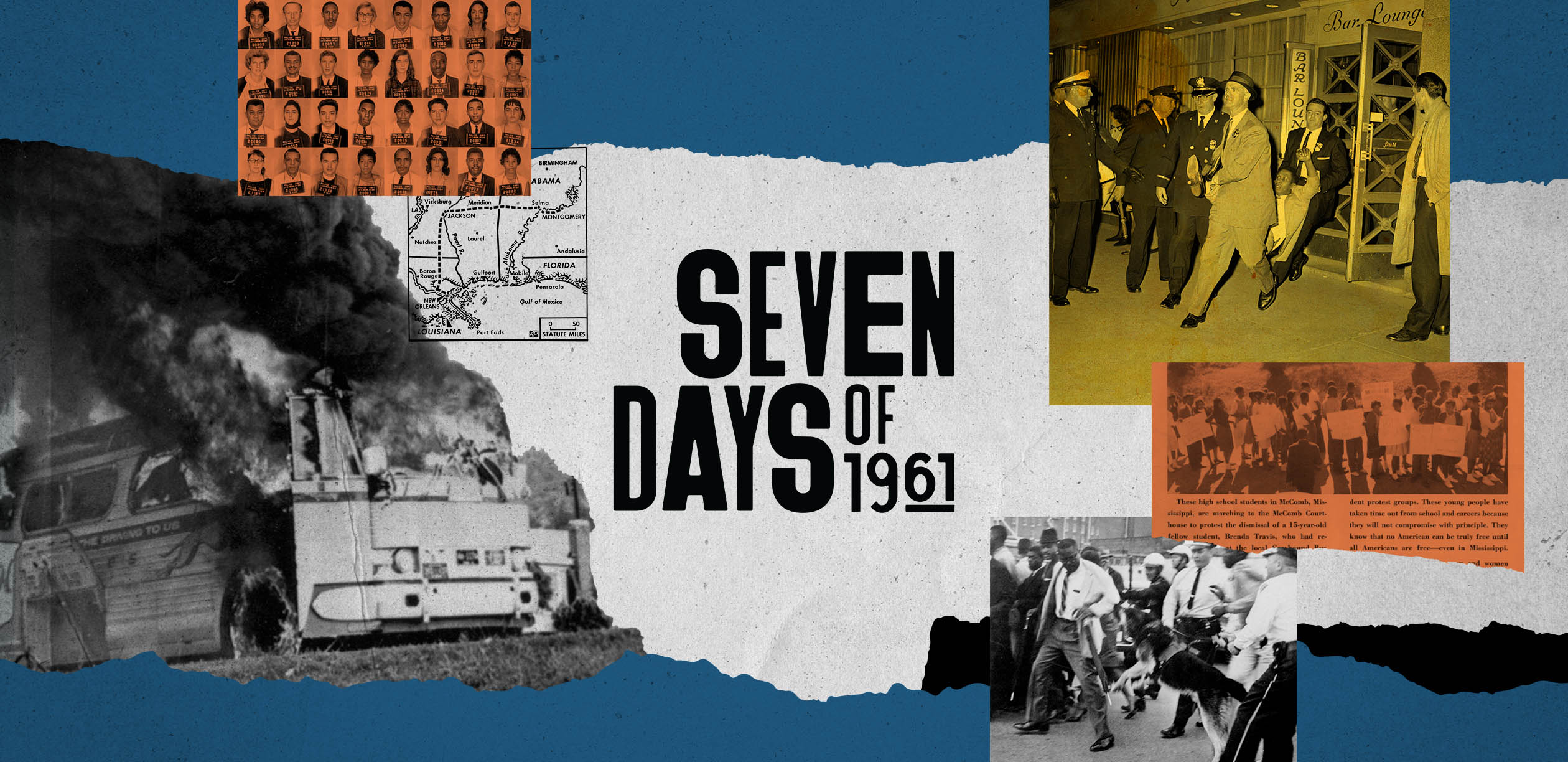

On today's episode of 5 Things: The courageous actions of Black women and men 60 years ago sparked pivotal civil rights battles against school and business segregation, police brutality and voting exclusion. Many of the activists were high school or college students risking their lives and futures.

People who fought for racial justice in 1961 take us back in history to the moments when they risked everything on the Seven Days of 1961 podcast, from USA TODAY.

We’re bringing 5 Things listeners a special preview of first full episode of Seven Days of 1961, “Violent white mob protests integration. Kenneth Dious ran to the crowd, ready to fight.”

In the episode, Kenneth Dious shares his story of the night he stood guard for a Black student who had just attended her first day of classes at the University of Georgia. He was only 15 years old when word spread in his hometown of Athens, Georgia, that a violent white mob had gathered outside the dorm room of Charlayne Hunter-Gault. Kenneth and three other Black men rushed to the crowd, ready to fight if needed.

New episodes of Seven Days of 1961 drop every Tuesday starting Nov. 2nd.

Click the buttons below to get connected with the show on your favorite podcast platform:

Hit play on the player above to hear the podcast and follow along with the transcript below. This transcript was automatically generated, and then edited for clarity in its current form. There may be some differences between the audio and the text.

Claire Thornton:

Hey there. I'm Claire Thornton, and this is 5 Things. It's Sunday, October 24th. These Sunday episodes are special, we're bringing you more from in depth stories you may have already heard.

Claire Thornton:

The Civil Rights Movement was nothing, if not a violent struggle. Across the Jim Crow South, college and high school students, faith leaders, shop owners, and so many others risked their lives to battle white supremacy. They fought for voting access and an end to racial segregation. In return, they lost their jobs or were kicked out of school. Their bodies were beaten up and bloodied. They were locked up for weeks or months, in prisons across the South.

Claire Thornton:

USA Today's, seven days of 1961 podcast produced by Natalie Boyd, is bringing you stories of civil rights battles straight from the people who lived them. They want to tell their stories because people all across America are still fighting for racial equality and voting rights 60 years later. You can follow the show now on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts. So go find the show on your phone. I'm about to give you a sneak peek of the first episode. Kenneth Dious was a high school student at the time Charlayne Hunter-Gault and Hamilton Holmes became the first black students at the University of Georgia. When news spread in the small town of Athens that a mob had formed outside of Charlayne Hunter-Gault's dormitory, Dious and four other young black men rushed to the crowd, ready to fight if needed. Here's that story from Kenneth Dious, in his own words.

Kenneth Dious:

We were going to put our lives at risk. The crowd seemed real-real. It wasn't just a [inaudible 00:02:20] as to what they were doing and they were throwing bottles and so forth. So I was afraid for myself and her.

Natalie Boyd:

This is Kenneth Dious, a freedom fighter. Every episode of this seven podcast series brings you to the center of a major civil rights event through the voice of an activist who lived it. Each had no clue what would happen next, all while facing the very real threat of death and violence. Their courageous actions helped to end segregation in America. I'm Natalie Boyd, a podcast producer with USA Today. This is the Seven Days of 1961 podcast. Hear history from the people who made it.

Kenneth Dious:

I am a long life resident of Athens, Georgia. I grew up in the civil rights movement here. I was a community activist and when I was a child, a young man, I marched against the Klan and participated in the sit-ins and the activities of the cities in regard to the integration of Athens, Georgia.

Natalie Boyd:

On January 11th, 1961, the first two black students of the University of Georgia, Charlayne Hunter-Gault and Hamilton Holmes began their first day of class. At nightfall, a riot targeting Charlayne Hunter-Gault erupted outside her dormitory. When news spread in the small college town of Athens that a mob had formed Kenneth Dious and three fellow high school classmates bravely rushed to the scene, ready to fight if needed.

Kenneth Dious:

Somehow we got the word that this crowd had appeared in front of cinema's hall in front of Charlayne Hunter dorm room. I mean, I'm at this time about 15 years of age. So some of us, other guys that were with me in the civil rights movement, activists, we decided to go over to see what was going on and when we arrived it must have been... It was dark, probably 9:00, 9:30, may have been 10 o'clock and we see this huge crowd standing outside of cinema's hall during and throwing things and so forth. And the minute that Charlayne Hunter comes out of the dormitory and leave, it was four us, four young black guys.

Kenneth Dious:

So we decided we going to hang around. We don't know this crowd is going to try to charge in that dormitory or not. Was she going to need some of our assistance, are we going to be brave enough to go in with that huge crowd to try to help her out if something occurred. There were no police at the time and they just stood out there and they cheered and they cheered and they cheered and they cheered. We were very afraid for Charlayne that night. The crowd seemed real- real. It wasn't just a [inaudible 00:05:31] as to what they were doing and they were throw bottles and so forth. Yes, I was afraid for myself and her. We were going to put our lives at risk and try to make sure that she was going to be safe.

Kenneth Dious:

We were to the side of the crowd, they saw us in a sense. If we had to run and do something we would have to get there pretty quickly because we still were a good little distance away, we would have not got there before they reached the front. Though any means, we have to run through the crowd. I mean, we could have easily got injured. Somebody could have hit me with a brick, bottle, or five people could have jumped on me or whatever, but we were going, if it came to that, yes, yes. Give me the power of mind to do that. But if we were going to be successful, we don't know. We were going to go and do what we had to do.

Natalie Boyd:

The violent white mob threw rocks and a Coke bottle shattered a window in Charlayne's dorm room. A group of men in crew cuts, held up a bed sheet with the N-word written across it and underneath it, the words go home.

Kenneth Dious:

But we had some prior experience in regard to this. We had been marching for a little while before this occurred and we had fought against the Klan before, we had had some rise with the Klan. The police had to come in and arrest some people up before this. So we knew what to expect. We weren't going to back down and that was a huge crowd. I think this is the biggest one ever for Athens. Matter of fact, they had blocked the street. They had backed up from the dump and they had blocked the street. Then there was a crowd up on the hill up to the next building and that was some on the sidewalk and some on the street. So it is a good size crowd. Yeah. Making their, I guess their feelings being known about Charlayne Hunter, to come to school here in the integration of the University of Georgia.

Natalie Boyd:

The crowd was a mix of KKK members, fellow students, and bystanders, about 2,000 people in total.

Kenneth Dious:

It went on for quite a while until seeing takes. I was coming up through there the minute that they break up that you start taking IDs. Then the police showed up kind of gently and so forth. Then it kind of slowly dissipates. Some, there was some struggle, took a while. It was almost, it could easily turned into a riot. I think the thing that probably cost the crowd to dissipate the most was that when Dean Tate said, he's going to start taking IDs and if you out here I'm going to start putting you out of school and that sort of backed the crowd out. I did not know that the Klan was out there until maybe a couple days later, something like that. They were not dressed out in that robes at that time but we later learned that they were there.

Natalie Boyd:

That night the Dean of students, Joe Williams, suspended Charlayne, and told her to immediately leave campus. Five days later, she and Hamilton Holmes returned to UGA emboldened by a federal judge's order that they be allowed to continue their education. Charlayne Hunter-Gault graduated from UGA with a degree in journalism. All of this occurred a full seven years after the Supreme Court's Brown versus Board of Education ruling, which banned segregation. UGA eventually led integration in the state of Georgia, but it was one of the last segregation strongholds to be broken in the country.

Kenneth Dious:

So I transferred to UGA, who did not want to accept me at the time, even though I had excellent grades and so forth to get in UGA. I had to almost threaten the, I don't want to call him an auditor, the admission person, let me use that term. He did not want to let me in, even though I had the test score, the grades, it took a while for me to convince him that he had to let me into UGA and that was going to be another battle with them. I got the letter saying you're admitted to UGA, but at that time there was other black students already at the UGA. I never went to class with another black student. There was some professors there. Things would change, thing of the sixties. If you are in their class and they didn't want you in their class, they didn't say anything. They may not encourage it, but didn't say anything. But the question with us, was still, were we going to get a fair grade?

Kenneth Dious:

I would say most of the time I got a fair grade. I give them credit for that. When I first got to UGA, going to class, they say, you have to take what they call stare material to class. And after my high school classmate, who was there, he said, that's something you for you to read before the professor told the class to order why they stared at you, what you call stare material, but it got better over the years, I would give UGA students some credit. You know, they kind of settled down with it after, just before I left, it was so then, and a lot of things changed and I had this friend of mine that had this great idea that we should go out for the University of Georgia football team.

Kenneth Dious:

So we went over to see, of course, I told him, come out for the football team. At that time, there was nobody playing any, any blacks was playing any sports in the south. But unfortunately when it came in the spring of 1966 to go out for the football team, my buddy was not in school. And my father told me that I had made that commitment, told somebody, something. So I had to go for the University of Georgia football team all by myself. So I was the only black player in the entire south that went out to integrate the University of Georgia football team. Of course again, I got my life threatened by the clan, so forth, cause I still was living at home that helped some. During my, during my years there, coach had made his mind that he was not going to play me or whatever, and my life was coming along. So I did not go back into the fall at all. I had hurt my knee. So I decided not to go back. That's my experience with University of George football team. Strange thing about athletics.

Kenneth Dious:

The players accepted me cause I could play, some encouraged me cause I could play. But you got to remember at the same time when I was at UGA, if you were, we had one or two members in the band and you could not go to Mississippi if you was in the band. And we were fighting this thing about, you know, every time we went to the stadium, they playing Dixie and all this stuff was going on. And we used to have quite a bit of debates, unfortunately fights, because you had a student there either interested in you or they were disinterested in you. Some thought you should be there and some thought that you should not be there. And so there were certain organizations we could not join. Fraternities still had the Confederate flag. We were fighting all the way through UGA, all of when I was student there. So I'll say this and a lot of people think I'm crazy. I said, thank God for UGA. I say in that regard, I mean, if I went to HBC, I would have had an average college experience. This one was very unique in that regard. And I feel like I really contributed to things at University of Georgia development. So where we are today compared to then, I am a little disappointed. In the sense of the enrollment of black students has gone down tremendously.

Kenneth Dious:

If you turn on the television and you look at the University of Georgia football team, you would say, oh, that's a great school. It is well integrated. And I'll make the statement that a friend of mine made one day. And see, I told her that and she says, Ken, the only thing that we got down here is football and basketball players, because you understand, when you see all these football players, basketball players, they get the special admittance from the president. If you're a great football player and you got a 2.5, they want you in the school, the president can specially meet, provided you meet the minimum. What we call SEC, southeast conference standards to play ball. That's how we got all these players here, but we don't have enough students. I mean, imagine, you almost got less black students than you got when I left my senior year. It's rapidly falling and nobody's saying it, but here's what they're doing. They name the education department after Mary Frances Early, and my law school at University of Georgia, they have pictures of justice, Benham. They have pictures of Chester Davenport, for the first black graduate. They have pictures of the first black female graduate. But do we have students? That's what's important. So is it all a show or does it have any meaning? That's where we are.

Natalie Boyd:

The Seven Days of 1961 podcast is produced and edited by me, Natalie Boyd. Stephanie Allen reported this episode and Jasper Colt produced the interview. You can see images of Kenneth and read Stephanie's full story about the first black student at the University of Georgia at Seven Days of 1961 dot USA today. dot com. Thank you for listening. Tell your friends about the podcast. We want more people to hear these personal stories about acts of resistance that changed our nation. Please write us a review on apple podcasts. It helps more people find the show and you can tweet us at USA today. On the next episode, you'll hear from an activist who was arrested after a sit-in at lunch counter, he and eight others chose going to jail, working 30 days of hard labor on a chain gang, instead of paying the $100 fine. This was a strategic choice that propelled the civil rights movement forward that's in the next episode, see you then.

Claire Thornton:

You heard what I said earlier. Go find the Seven Days of 1961 podcast cast right now, wherever you listen to podcasts, that way you can get connected with more episodes that drop next week. I've also linked directly to the show in the episode notes. If you liked what you heard, tell your family, tell your friends about Seven Days of 1961. We want to share these stories of civil right struggles far and wide. And if you want rate and review seven days of 1961 on apple podcasts and thanks to the folks who wrote new reviews of five things floating head DM wrote this podcast is how I get my news while getting ready for work. It's quick and convenient. And my wife says I can't multitask. Thank you so much. And another reviewer wrote that five things is quote a gem, go write us a review on apple podcasts, telling us what you like about five things. And you'll get a special shout out on the show. Taylor Wilson will be back tomorrow morning with five things you need to know for Monday. Thanks for listening. I'm Claire Thornton. I'll catch you next time until then you can keep up with me on Twitter where I'm at Claire underscore T H O R N T O.

Source link