The United States is aiming to launch a group of small satellites to fill a critical gap in the ability to foresee precipitation dangers, like the deluge that overwhelmed Northeastern cities at the start of September.The U.S. Air Force announced Thursday a nearly $20 million contract with Tomorrow.io to develop and deploy an entire constellation of small satellites equipped with advanced radar to measure precipitation from space.Currently, there is only a single satellite equipped with that capability among the more than 3,000 active satellites orbiting the Earth."This is a problem," a NASA official told CNN. "It's a big-dollar thing to do and, so far, the agencies have been unwilling to do more."That orbiting satellite, known as the Global Precipitation Measurement Core Observatory satellite, was launched in February 2014 by NASA and Japan's counterpart, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency. The observatory cost nearly a billion dollars and is larger than a school bus — but it can do what no other satellite can. Unlike most weather satellites, which can only observe the outermost layer of a storm, the GPM satellite can "see" inside the clouds to predict more precisely when, where and how much rain or snow will fall. The satellite also unifies data measuring precipitation by an existing group of satellites, run by a consortium of international partners.That kind of data is critical in forecasting extreme weather events. When the remnants of Hurricane Ida swept through the Northeast and killed at least 52 people from Maryland to Connecticut, the National Weather Service warned of "heavy rainfall and potentially significant flash, urban, and river flooding" a full 24 hours in advance. But the historic amount of rain that fell in New York City — more than 3 inches in a single hour — still caught city and state officials by surprise."We did not know that between 8:50 and 9:50 p.m. last night, that the heavens would literally open up and bring Niagara Falls level of water to the streets of New York," New York Gov. Kathy Hochul said after the grave loss of life.The more precipitation radars there are in space, the more accurate the forecast will be on Earth.The United States is equipped with a network of ground-based precipitation radars. But many parts of the world are not, including the two-thirds of the Earth's surface covered by oceans. Those areas — and vast swaths of China, Russia and Africa — are virtually untouched by terrestrial precipitation radars, and they are regions of great interest for the U.S. military."When you go to these regions, there is no functioning weather systems on the ground. And even if they do exist, the U.S. doesn't really have access to them. And that impact, I can tell you as a pilot myself, that impacts every single decision you do in the military," Rei Goffer, a former pilot in the Israeli Air Force and the cofounder of Tomorrow.io, told CNN."What we have done is miniaturized the radar instrument," Goffer said. "We've taken it from a school bus-size instrument to something that's about the size of a mini fridge."The reduction in size makes the satellites far less expensive to launch. Goffer believes his company can assist the U.S. military and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration the same way SpaceX has helped NASA — by providing cost-effective solutions to decades-old problems and freeing up the federal agencies to focus on long-term priorities."We really see ourselves as the SpaceX of weather," Goffer said. "Weather is one of the last domains that has not seen massive investment and massive innovation coming from the private sector, until now."Tomorrow.io's first satellites are scheduled to launch in late 2022, and the company hopes to have the full constellation of approximately 32 small satellites operational by the end of 2024."I would not bet against them," a NASA official told CNN. "But it's extremely challenging."It takes the GPM's core satellite, on average, two to three days to "refresh" or scan the entire planet. Tomorrow.io is aiming to get that refresh rate down to once an hour. The expansion of global radar coverage could greatly improve the accuracy of forecasts, especially as climate change contributes to more extreme weather."One of the things you had with Ida is that these storms are changing more frequently and more volatilely than in the past," Dan Slagen, Tomorrow.io's chief marketing officer, said. "So being able to have the faster refresh rate, especially coming from space, will help us on those types of storms tremendously."

The United States is aiming to launch a group of small satellites to fill a critical gap in the ability to foresee precipitation dangers, like the deluge that overwhelmed Northeastern cities at the start of September.

The U.S. Air Force announced Thursday a nearly $20 million contract with Tomorrow.io to develop and deploy an entire constellation of small satellites equipped with advanced radar to measure precipitation from space.

Currently, there is only a single satellite equipped with that capability among the more than 3,000 active satellites orbiting the Earth.

"This is a problem," a NASA official told CNN. "It's a big-dollar thing to do and, so far, the agencies have been unwilling to do more."

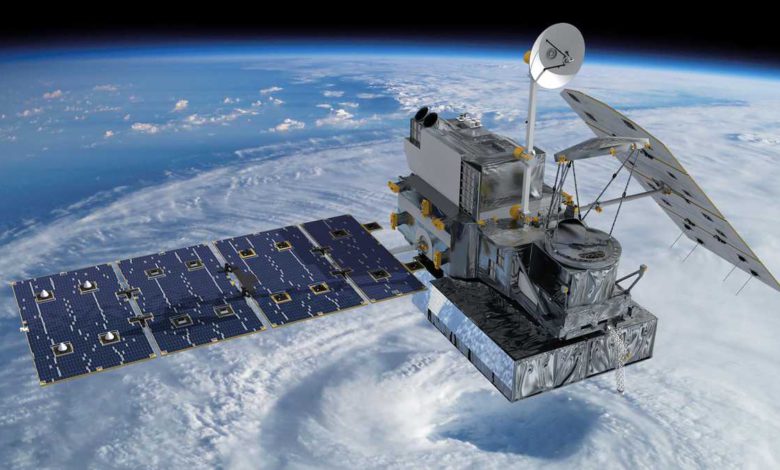

That orbiting satellite, known as the Global Precipitation Measurement Core Observatory satellite, was launched in February 2014 by NASA and Japan's counterpart, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency. The observatory cost nearly a billion dollars and is larger than a school bus — but it can do what no other satellite can. Unlike most weather satellites, which can only observe the outermost layer of a storm, the GPM satellite can "see" inside the clouds to predict more precisely when, where and how much rain or snow will fall. The satellite also unifies data measuring precipitation by an existing group of satellites, run by a consortium of international partners.

That kind of data is critical in forecasting extreme weather events. When the remnants of Hurricane Ida swept through the Northeast and killed at least 52 people from Maryland to Connecticut, the National Weather Service warned of "heavy rainfall and potentially significant flash, urban, and river flooding" a full 24 hours in advance. But the historic amount of rain that fell in New York City — more than 3 inches in a single hour — still caught city and state officials by surprise.

"We did not know that between 8:50 and 9:50 p.m. last night, that the heavens would literally open up and bring Niagara Falls level of water to the streets of New York," New York Gov. Kathy Hochul said after the grave loss of life.

The more precipitation radars there are in space, the more accurate the forecast will be on Earth.

The United States is equipped with a network of ground-based precipitation radars. But many parts of the world are not, including the two-thirds of the Earth's surface covered by oceans. Those areas — and vast swaths of China, Russia and Africa — are virtually untouched by terrestrial precipitation radars, and they are regions of great interest for the U.S. military.

"When you go to these regions, there is no functioning weather systems on the ground. And even if they do exist, the U.S. doesn't really have access to them. And that impact, I can tell you as a pilot myself, that impacts every single decision you do in the military," Rei Goffer, a former pilot in the Israeli Air Force and the cofounder of Tomorrow.io, told CNN.

"What we have done is miniaturized the radar instrument," Goffer said. "We've taken it from a school bus-size instrument to something that's about the size of a mini fridge."

The reduction in size makes the satellites far less expensive to launch. Goffer believes his company can assist the U.S. military and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration the same way SpaceX has helped NASA — by providing cost-effective solutions to decades-old problems and freeing up the federal agencies to focus on long-term priorities.

"We really see ourselves as the SpaceX of weather," Goffer said. "Weather is one of the last domains that has not seen massive investment and massive innovation coming from the private sector, until now."

Tomorrow.io's first satellites are scheduled to launch in late 2022, and the company hopes to have the full constellation of approximately 32 small satellites operational by the end of 2024.

"I would not bet against them," a NASA official told CNN. "But it's extremely challenging."

It takes the GPM's core satellite, on average, two to three days to "refresh" or scan the entire planet. Tomorrow.io is aiming to get that refresh rate down to once an hour. The expansion of global radar coverage could greatly improve the accuracy of forecasts, especially as climate change contributes to more extreme weather.

"One of the things you had with Ida is that these storms are changing more frequently and more volatilely than in the past," Dan Slagen, Tomorrow.io's chief marketing officer, said. "So being able to have the faster refresh rate, especially coming from space, will help us on those types of storms tremendously."

Source link