As Dawn Tucker jogged her usual route in Staunton, Virginia's Thornrose Cemetery, she heard a voice say, "Turn around."

Tucker did, but no one was there. Her gaze fell upon a tombstone she'd jogged past countless times before but hadn't noticed. It read:

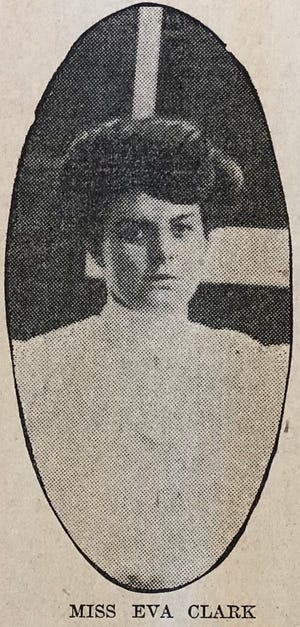

Eva Clark

DIED

Oct. 1, 1906,

Aged 25 years

Beneath the straightforward engraving was an intriguing inscription: "Erected 1923 by friends with Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus."

"I was instantly fascinated," said Tucker, 36, of Flagstaff, Arizona. "First, because I'd had that kind of ghostly experience, and then because the stone was erected by a circus and it had taken 17 years to put it up."

So Tucker, an artist by trade, started doing research and happened to connect with another woman who also wanted to learn more about the woman buried beneath the mysterious tombstone.

Two years later, they've pieced together a tale of intrigue and murder that ties back to Cincinnati.

"Her life was so much more interesting than her death," said Aíne Murphy Norris, 34, who is leaving behind a job teaching English and American literature at Pensacola State College in Florida to return to her home state of Virginia.

"She was a big deal in the entertainment industry, but all I had heard about her from this kind of lore was her death. My goal was to figure out what happened in her life."

Here's the story they've unearthed:

Eva Clark was born Eva Kelley, daughter to circus and vaudeville entertainers Lee Howard Kelley and Alice Howard. The early 1900s were rife with anti-Irish sentiment, so the family eschewed their given surname and went by "Howard" instead.

Eva's exact date and location of birth aren't known, but her home base was Cincinnati. Her parents performed with the Clements & Russell Railroad Show in 1890, when their daughter was younger than 10.

Soon, the Howards began performing alongside "Eva May" or "Little Eva" in various traveling companies. Based on advertisements bearing her name and many aliases – which were typical of circus performers at the time – Eva Howard was multi-talented. She sang and danced and was such an accomplished aerialist that reporters repeatedly referred to her as "The Queen of the Air."

One news story read: "She seems to feel as much at home in the trapeze acts as if she we're on the ground."

When in Cincinnati, Eva performed at the Commodore Concert Hall on Vine between Fifth and Sixth streets, which shuttered in 1905.

In the late 1890s, she began traveling with the Clark Bros. Circus. In 1897, when Eva was at most 16 years old, she married Lum Clark, son of that circus' owners.

It wasn't a happy marriage.

"In the divorce decree, Eva files for divorce because Lum had refused to live with her since their wedding, had beaten her many times, had threatened her and had shot at her," Tucker said.

The decree was filed in 1903 but the two apparently never divorced.

Three years later, when the circus was performing in Staunton, Virginia, Eva would be found writhing on the ground in a circus tent, a bullet in her abdomen.

The shooting, though not immediately fatal, made headlines far beyond Virginia. Eva survived at first and refused to say much about what had happened to her, beyond that it was an accident.

She died a month later during a second surgery caused by an infection of her wound.

A headline in The Enquirer on Oct. 3, 1906, read: BULLET Ends Eva Clark's Life, And Mystery Surrounds the Tragic Fate of a Pretty Circus Performer from Cincinnati."

News of her death left those who knew her heartbroken. In particular, a Price Hill woman named Elizabeth Brannigan, whose husband Edward ran the Commodore Concert Hall.

The Brannigans told reporters they wanted to bring Eva's body back "home" to be buried, but Staunton authorities refused. Police said they weren't convinced the shooting had been accidental and needed to keep the body as potential evidence.

Despite that, no one was ever charged in Eva's death.

Eva was buried in an unmarked plot. It'd be 17 years before members of another circus raised money to finally erect the tombstone that interrupted Tucker's jog.

After years of research, Tucker and Norris are dubious the shooting was accidental. For starters, witnesses said two men were with Eva when she was shot – her husband, Lum Clark, and a man of whom Clark was jealous, a fellow trapeze performer named James Richards.

(Clark's jealousy was well known, as noted in The Enquirer: "Clark loved his wife devotedly, but when his jealousy was excited was prone to make implied threats.")

Second, Lum Clark fled after the shooting, reportedly hightailing it to Mexico.

Plus Eva herself had said in her divorce filing that Clark had shot at her.

"You don't purposefully shoot at someone once and then accidentally shoot at them the next time," Tucker said.

As much research as she and Norris have done, they're hoping to still do more: They're looking for Cincinnatians with ties to the Howard family, the Brannigans and the Commodore Concert Hall, as well as Price's Floating Opera, where Eva and her mother performed under the surname Adair.

Their goal, Norris said, is to ensure that the young circus performer is remembered for her life, not just her tragic death.

"The collective memory is incomplete," she said. "I think it's kind of our duty as researchers, if we have the ability, to change someone's narrative for the better and to be more accurate."

Source link