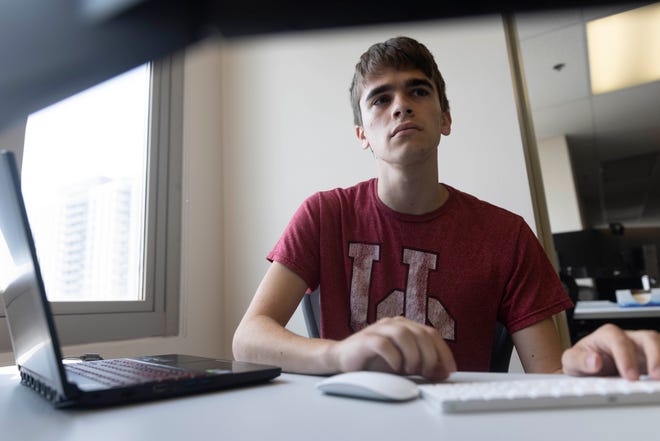

Colby Nolasco says he heard about University of Cincinnati's Early Information Technology program during his sophomore year of high school, in math class.

His interest piqued when the presenter said he could learn how to code his own video games.

"Yeah, sure, why not?" Nolasco says he thought at the time.

He opted into the program and started taking IT classes his junior year, earning the credits equivalent to one year of college by the time he graduated from Lebanon High School in spring 2020. Ten of his classmates did the same.

Now he's a year into a co-op with the university's Information Technology Solution Center and says he will graduate the five-year master's program a year early, jumping into the industry as soon as he can.

That's good, program director Hazem Said says, because the IT industry needs strong, new talent now.

According to a report from Korn Ferry, a consulting firm that specializes in talent acquisition, more than 85 million worldwide jobs could go unfilled by 2030 "because there aren't enough skilled people to take them." Jobs in tech are being left unfilled at a particularly alarming rate.

More from USA TODAY: Breaking down the big US labor shortage: Crunch could partly ease this fall but much of it could take years to fix

Daxx, a tech consulting company, acknowledged a major talent shortage that stacked up to 1.4 million unfilled U.S. computer science jobs by the end of 2020, while graduating students in the field tend to number about 400,000 per year.

"Business development and digital transformation are impossible without new talent, which intensifies the gap between tech talent supply and demand," the company wrote of the national shortage.

Said says he's heard of this struggle from local industry partners for nearly a decade now. In that time, he's crafted the Early IT program and recruited over 30 local school districts to sign on, offering any student who joins and does well automatic admission into the university.

Cincinnati Public Schools was the first school district to partner with the university, in 2017.

“If our talent in Cincinnati, in Ohio, in the United States is not globally competitive, it will impact our ability as a country, as an economy, as a culture, as a philosophy to thrive in the world of tomorrow," Said says.

There are over 1,100 high school students in the program and 1,200 university students in UC's IT college. Said says the program is expanding at an average annual growth rate of 18%.

What is IT?

IT is the use of computer systems and technology to solve human problems, Said says.

Said uses a cellphone to explain. The phone itself is made by a computer engineer, he says. The operating system is created by a computer scientist. But the applications people use their phones for on a day-to-day basis – checking the weather or mapping directions, as examples – are information technology.

IT is an acquired skill that anyone can learn, Said says, if they put in the work. It's like playing basketball or learning an instrument. Most high schools have programs that focus on those skills from a young age; some even in elementary school.

"We want to do the same for IT," he says.

Wins all around: Schools, students and industry

Schools that partner with the Early IT program can choose to offer the first year of IT courses at their high school buildings, through their own staff. Said says that's a win for schools because it offers ultimate flexibility and training for their teachers, through UC's graduate certificate program.

Other students in the program take classes at satellite campuses.

Though the Early IT program is set up to remove certain barriers for students by granting automatic admission, financial challenges are still present. There are few scholarships available in the college. Said says the university is looking to find financial partners so it can continue to recruit more diverse students to the program.

But Nolasco and Vismaya Manchaiah, a third-year IT student at UC, both say they've never been worried about the financial impact of college since their co-ops have offset the cost of tuition. Plus, their first year was free, since they completed those classes in high school.

Said says local partners have poured over $8 million into the college's students through co-ops. In IT, average wages earned equate to between $9,000 and $11,000 per semester. And once they graduate, Said says his students who pursue IT often end up with "transformative salaries."

"By transformative salary, I mean not a minimum salary that gets you to live, but a salary that allows you to transform your life and the lives of your family and your community. And that’s very important," Said says.

"A lot of people think you can earn a transformative salary only through sports or entertainment. And I say actually, IT can offer much higher transformative salaries over a much longer period of time than these other disciplines.”

Nolasco's most recent class, learning Javascript, was "a breeze," he says, because he had already learned some tricks through his co-op.

He says he never would have known how to pursue a career in tech without that experience at Lebanon High, since no one in his family is in the field. He's hoping to go into software development.

Manchaiah, of Springboro, says she'd like to pursue data analytics. She's already had two co-ops and has served as a mentor to incoming students in the program.

By giving students the skills, experience and confidence to pursue IT, Said says many students graduate with three or more job offers. That's a win for them and for the industry, he says.

"These (students) are the ones that will carry us moving forward as a society," Said says.

Source link