Even with the stress of the pandemic, suicide counts in 2020 in five local counties were at or near five-year lows, Experts say the results from Boone, Butler, Clermont, Hamilton and Warren counties could be due to more state resources for suicide prevention and stepped-up telemedicine for mental health care.

Yearly suicide counts are an imprecise measure of the region’s mental health, and professionals have worried about the pandemic making mental health problems worse, including suicide. In Mason last year, 15 students were hospitalized for suicidal thoughts, and the school superintendent pleaded with parents and children: "Please let us help."

Yet last year across the Cincinnati region, the suicide numbers dropped. Experts cautioned against reading too much into that result because many elements contribute to the suicide rate, and the 2020 numbers are within the ranges over time. Still, caregivers say that nearly a year into the pandemic, their clients are tapping into wells of resiliency.

“People are beside themselves in the sense of: How do I make change in my life when I’m so limited? Are there things I can do for myself?” said Traci Sippel, a licensed counselor in Hyde Park. “I’ve had a lot of clients asking me for letters to their landlords about getting a pet in their apartments.”

“I am just not seeing the high rates of suicidal thinking, let alone suicide attempts,” said Dr. Phil Lichtenstein, medical director at the Children’s Home of Cincinnati. “I’ve been surprised how few have had to go to the emergency room for acute assessment, and how few overall had to be admitted for stabilization.”

Children, who see everything, are taking in the pandemic’s widespread economic pain and disruptions, Lichtenstein said. “There’s no question kids are very much aware of the fact that everybody’s suffering, that they hadn’t been singled out for bad outcomes or bad circumstances.”

The Enquirer surveyed the seven counties in the immediate Cincinnati region for their preliminary 2020 suicide counts. Boone County joined Hamilton County in hitting a five-year low for suicide last year. In Butler, Warren and Clermont counties, the 2020 count was lower than 2019. Calls to the coroners in Kenton and Campbell counties were not returned.

More on hand at the start

A low suicide count does not mean the society is without stress. In fact, surveys have consistently found more stress among Americans especially among parents and children as the pandemic imposed economic hardship and reshaped school schedules.

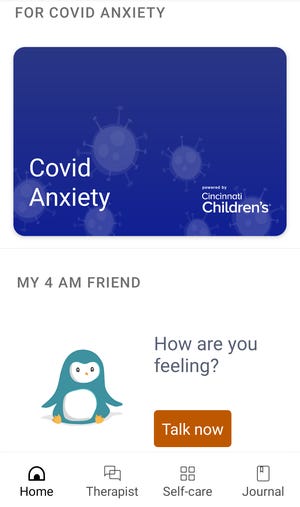

But the region and the state of Ohio went into the pandemic having already devoted more resources for mental health care and suicide prevention. Just last February, ahead of the state shutdown, the Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services set up a statewide prevention plan with 30 public and private organizations.

The goal, Criss said, is to better identify Ohioans considering suicide, especially younger people and military veterans, and to ensure access to care. With the arrival of the pandemic, the department added additional resources. “We knew there would be increased anxiety and depression, just like any natural disaster,” Criss said.

'A big learning'

Dr. Michael Sorter is director of the division of child and adolescent psychiatry at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. He said the hospital was busy through 2020 until just before the holidays, and he warned against using the yearly suicide count as a barometer of 2020’s mental health status.

But he said the expanded use of telemedicine in mental health care did bring down the number of appointment no-shows. “It’s been a big learning for all of us,” he said. “We’ll find out as we go forward what’s the best balance.”

The problems with telemedicine are akin to the problems of virtual schooling, Sorter said. Some children don’t have a device or an internet connection, or their families move around. “Kids are reflections of what stress their families are under,” he said. “And now, it’s a little more hidden, the families who can’t make ends meet and parents under high stress and unemployment, dealing with their own mental health sufferings because they don’t have the supports they need.”

Sorter said he advises that hard as it may be some days, parents and children “when they’re discussing the struggles, to focus on the communication, on being together, on being part of a family, and that things can improve.”

If you are considering suicide or are in crisis, the national help line is (800) 273-8255.

Source link