A year ago, the U.S. Capitol was the kind of place where a suspicious flicker on a radar screen was all it took for police to lock doors and stop traffic on surrounding streets.

“We’ve got alerts for anything you can imagine,” Capitol Police Chief Steven Sund told a congressional committee in February, explaining an incident Nov. 26, 2019, that sent parts of the Capitol into a half-hour lockdown while police investigated.

Being ready to take decisive action quickly was crucial, Sund told Congress during budget hearings last year, as he disclosed a 75% increase in threats to the Capitol under President Donald Trump. Sund told congressional leaders that he needed a $54 million budget boost, including $7 million atop an eight-figure materials budget to upgrade equipment and supplies. No one in the hearing objected.

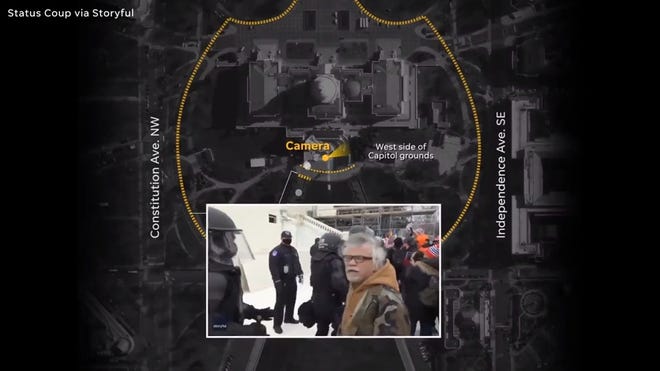

Yet three weeks ago, when the threats turned into the single largest attack on the main building under the agency’s protection, hundreds of officers were sent into the chaos with little if any protective gear. Their bare knuckles gripped the tops of lightweight metal barriers that the rioters peeled off and used to beat them. A few officers threw punches, eyes wide behind blue surgical paper masks – the only shield between them and the throng of insurrectionists.

Read:How police failures let a violent insurrection into the Capitol

Flashes of heroism by the force during the siege added to questions of how Capitol Police could be overrun by a loosely knit mob of far-right extremists, rioters and hangers-on. The answers will be picked apart by the public, inspectors general and Congress for years to come, starting with a closed-door House Appropriations briefing Tuesday about what went wrong.

Whatever the department’s shortfalls, money wasn’t one of them: Capitol Police spend as much as the entire Dallas Police Department to protect a 2-square-mile jurisdiction: the Capitol and its perimeter.

Growing threats against members of Congress was a bargaining chip for Sund in asking lawmakers for a budget increase for this year, as it had been for his predecessor, Matthew Verderosa. In 2019, Verderosa pushed for millions extra to prepare for the 2020 Republican and Democratic National Conventions and January’s inauguration.

The agency’s budget is shrouded in secrecy, largely because it is exempt from the laws that require most other state and federal law enforcement agencies to disclose records. A nearly 600-page list of itemized expenses from October 2017 to March 2018 offers a snapshot of how money flows through the department.

In 2017, the year Sund told Congress the department began experiencing the uptick in threats, Capitol Police spent nearly $10 million over a six-month period on tactical gear, cyber infrastructure and related supplies. It spent an additional half-million dollars on controlled explosives and ammunition and almost a quarter of a million on external training.

Among the largest contracts was nearly $4 million to a company that provides electronic security, audio and visual surveillance and cyber intelligence. Almost $1 million went for X-ray security screening machines.

This year, Sund earmarked $22 million of the department’s nearly $516 million budget for equipment.

“They should’ve had everything they needed to protect the Capitol,” Rep. Maxine Waters, D-Calif., told USA TODAY. “Those barricades were so flimsy; it was a horrible scene.”

What went wrong, and who’s to blame?

Ed Bailor watched the Capitol riot with tears in his eyes as outmanned and under-equipped police were overrun and beaten on live television.

Bailor led the threat assessment unit for the Capitol Police until he retired in 2005. In his 32-year career there, he commanded everything from the 400-man civil disturbance unit to the horse-mounted officers.

After preparing for eight inaugurations and the Million Man March in 1995, Bailor has doubts that leaders of his former agency could have failed to anticipate the threats leading up to Jan. 6. The force also has spent millions beefing up physical security, he noted, such as reinforced concrete walls and steel fences around the building.

“It was police management problems, officer problems and members of Congress problems,” Bailor said. “There are ways to secure the building that could have been done faster and sooner.”

Sund resigned in the fallout from the Jan. 6 Capitol siege, as did Senate Sergeant-at-Arms Michael Stenger and House Sergeant-at-Arms Paul D. Irving. Stenger, Irving and Capitol Architect J. Brett Blanton make up the Police Board that coordinates protection plans for major events. Sund, as chief of police, was the fourth, non-voting member of the board.

At least 17 Capitol police officers have been suspended while investigators look into how they handled the invasion. Officer Brian Sicknick, 42, died that day after rioters bludgeoned him with a fire extinguisher and 81 Capitol Police officers were injured, according to court records.

In her first public statement since taking over the department earlier this month, acting Capitol Police Chief Yogananda Pittman on Tuesday apologized for the failures. The agency should have done more to protect the Capitol, she said.

'We did not do enough': Acting Capitol Police chief apologizes to lawmakers for handling of Jan. 6 riot

Pittman said Capitol Police had asked 1,200 officers to be at the ready for an attack, but only four of the platoons were outfitted with riot gear and less lethal ammunitions – less than a quarter of the officers. She also expressed the belief that nothing could have prepared them to prevent a protest of that size overrunning the Capitol.

The Capitol, she said, even in its layout and design was made to be open and welcoming to citizens.

"I doubt many would have thought it would be necessary to protect it against our own citizens," Pittman said in the statement. She later added of the fallout from Jan. 6: "We know the eyes of the country and the world are upon us"

Sund did not return several telephone calls from USA TODAY seeking to understand why the force’s advanced equipment was not on wide display on Jan. 6.

In interviews with NPR and The Washington Post, Sund said he wanted to send more officers out in riot gear but Stenger and Irving were concerned about how it would look, a claim that Pittman confirmed Tuesday. They would have needed to agree on a major show of force.

Sund also said he tried to get military support lined up ahead of time.

The Post reported last week that Charles Flynn was one of the top military leaders in the room when the Army rebuffed Sund’s request for help as the rioters descended on the Capitol. Flynn’s brother, former Trump national security advisor Michael Flynn, pleaded guilty to lying to the FBI in 2017. He received a pardon from Trump in November and called for Trump to declare martial law and force a redo of the election.

Waters disputes Sund’s claims that he tried in vain to get help before the riot. She said when she spoke with him ahead of time, he only mentioned Washington, D.C. Metropolitan Police as a source of backup.

If Sund did know the severity of the coming threats and was unable to get outside help, however, Waters said he and the board should have stepped up their own efforts. Barricades should have been stronger, she said. And every single officer on the ground should have been armed with the best protective gear available.

Handling threats portrayed as top priority in budget hearings

Speed and intensity, especially in response to potential threats, was a consistent theme in Sund’s remarks to the House Committee on Appropriations last February.

When a congressman asked Sund to explain the November 2019 lockdown, he described it as “a day I’ll remember for a long time.”

That morning there had been a tip about a possible aircraft moving bizarrely near the Capitol. Then, something – no one knew quite what – showed up on a radar screen.

Capitol Police sprung into action. For between 23 and 26 minutes, officers stood ready to evacuate the building at a moment’s notice. And then, nothing happened.

“It was nothing?” House Appropriations Committee Chair Tim Ryan, D-Ohio, asked in a video of the February hearing.

Sund shook his head and said it was nothing.

“It wasn’t a drone, it wasn’t a —” Ryan continued.

“It was nothing, yup,” Sund responded. “It was a radar anomaly that wasn’t even in the area.”

By the end of the year, records show, Congress had approved most of Sund’s proposed budget for this year. A large portion was slated for an increased contribution to the federal employees’ retirement system, Sund said.

It remains unclear now how the rest of the money – or the specialized equipment detailed in the 2017-2018 expenditures – may have figured into Capitol Police’s response on Jan, 6.

For instance, three years ago, about $825,000 went to Smith’s Detection, Inc., an Edgewood, Md.-based company that makes X-ray security screening machines and other threat-detection equipment, according to the company’s website. Yet rioters who entered the Capitol were photographed carrying spears, poles and stun guns. One stands accused of bringing in a gun.

Another $3.8 million went to MC Dean, Inc., a Tysons, Va. company that provides electronic security, audio and visual surveillance and cyber-intelligence. Yet Capitol Police appeared caught off guard as rioters scaled walls, pushed into tunnels and bashed in windows in seemingly coordinated moves.

Daniel Schuman, policy director of the progressive advocacy group Demand Progress, told USA TODAY that the Capitol Police has essentially been building an empire, and Congress rarely opposes their budget requests.

“This is the democracy death spiral,” Schuman said. “All this money is being siphoned off to go to the Capitol Police, and not only did they fail, but also they’re incredibly expensive.”

Despite the false alarm in 2019, everyone at the February hearing agreed with Sund’s better-safe-than-sorry approach to threats. That had been Sund’s mantra since he joined the U.S. Capitol Police as an assistant chief and continued after he became chief in June 2019.

Sund told the House committee that his officers had thwarted “a number of serious and credible threats” against lawmakers in cases that not only made national headlines but led to charges.

Just days before Sund’s February testimony, Jan Peter Meister, of Arizona, had been charged with threatening Rep. Adam Schiff, D-Calif. that he would “blow your brains out,” in a voicemail reacting to a Fox News segment. Meister would go on to spend six months behind bars before a judge sentenced him to time served plus three years supervised release, the forfeiture of his firearms and a $100 fine.

In the hearing, Sund asked for and later received a more than 11 percent increase in the department’s budget — from $462 million to $516 million. The money, he said, included salaries, training-related overtime and security for the 2021 Presidential inauguration.

“For any part of the federal budget, that increase is huge,” noted Chris Edwards, director of tax policy studies at the Cato Institute.

Despite the massive budget, some suggest that cost remains part of the decision-making process for Capitol Police. Bailor speculated that the failures on Jan. 6 may have been rooted in a basic budget consideration: reluctance to spend more on overtime, especially with the inauguration looming.

Threats consume resources, rarely result in charges

Capitol Police officials say the force spends hours every day sifting through threats lodged by angry or deranged Americans, many of them citing specific, actionable harm. When their agents testify in threat case hearings, they make it clear that their mission extends well beyond the Capitol building itself.

“We protect the 535 members of Congress, their employees and their families, both here on Capitol Hill, as most standard police departments, and then nationwide, through our protection details and our investigations,” said Special Agent Christopher Desrosiers, who tracked down Meister in Arizona.

Because Congress has exempted its police force from public scrutiny, no public accounting of time spent on threats exists.

USA TODAY in 2017 began requesting all investigations from cases the Capitol Police passed on to the FBI to gauge the level and tenor of threats. Those documents reveal that while the FBI swiftly takes action on those cases, federal prosecutors rarely pursue charges.

In the resulting sampling, which spans decades, more than 80 members of Congress have been seriously threatened. Based on the thousands of pages of investigative information sheets provided, those threats ranged from unhinged social media posts to letters and phone calls.

One man warned Sen. Cory Gardner, R-Colo. in a note that he should “get ready for a head stomping,” and threatened his family. Another called Sen. Amy Klobuchar’s office and said he would “put her in a body bag.”

After Trump took office in 2017, an Associated Press report indicated then-Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell would work to repeal president Obama’s signature health care law. Quoting the clip, a Twitter user wrote: “Yeah um I’m gonna kill Mitch McConnell don’t you dare.”

It was detected by the U.S. Senate Office of Protective Services and Continuity, forwarded to the U.S. Capitol Police, who in turn notified the FBI. The writer turned out to be a Kent University student in Akron, Ohio who admitted to the FBI that she had made the threat but never intended to carry it out and had no access to weapons.

After a nine-day investigation, the U.S. Attorney’s office declined to prosecute.

In 2019, staff for Rep. Rashida Tlaib, D-Mich., received a voicemail that threatened the the congresswoman's life. Capitol Police investigated, preserved the voicemail and sent it to the FBI. The FBI tracked the phone to a San Jose woman and interviewed her. Again, no charges were filed.

The fact that charges are rare frustrates law enforcement officers, Bailor said.

“I have to go tell that member of Congress, “You know that guy from Minneapolis who said he’s going to shoot you and your wife? Well, that’s not being pursued any more,’” Bailor said.

Waters expressed disappointment about the agency’s handling of a threat she faced in 2018.

After someone attempted to mail a bomb to her office and she received multiple death threats, Water said she began asking Capitol Police officers to see her home on nights she worked late on Capitol Hill.

Initially, they were happy to oblige, Waters said. But later one told her that Irving, the House sergeant at arms, had found out about it and told them to stop. Irving did not respond to requests for comment from USA TODAY.

“He took away whatever small measure of protection I had,” Waters said.

Waters raised the matter with Bennie Thompson, chairman of the House committee on Homeland Security. He told her that there were too many members of Congress for the police to provide that level of security for each of them. Thompson did come up with $25,000 to pay for protection when lawmakers are going to and from official duties.

“Official duties,” Waters repeated. “Well, I have to be careful even when I go to the grocery store.”

Contributing: Nicholas Wu, Kenny Jacoby

Source link