MINNEAPOLIS — The first week of witness testimony in the trial of Derek Chauvin, charged with the murder of George Floyd, ended Friday afternoon with a veteran Minneapolis police officer who explained the training officers receive.

Lt. Richard Zimmerman told the court that kneeling on the neck of a suspect is potentially lethal and there is "absolutely" an obligation to provide medical intervention as soon as necessary. Zimmerman called Chauvin's use of force on Floyd “totally unnecessary."

“Holding him down to the ground face down and putting your knee on the neck for that amount of time, is just uncalled for," he said.

Friday concluded a week of testimony from 19 people, including many who witnessed the Floyd's arrest on May 25, 2020. Several of them have cried or became emotional on the stand describing their attempts to intervene on his behalf.

Chauvin is charged with second-degree murder, third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter. Floyd, who was Black, died in police custody after Chauvin, who is white, pinned his knee against Floyd’s neck for more than nine minutes.

Judge Peter Cahill adjourned court until 9:15 a.m. CST Monday.

Stay updated on the Derek Chauvin trial: Sign up for text messages of key updates, follow USA TODAY Network reporters on Twitter, or subscribe to the Daily Briefing newsletter.

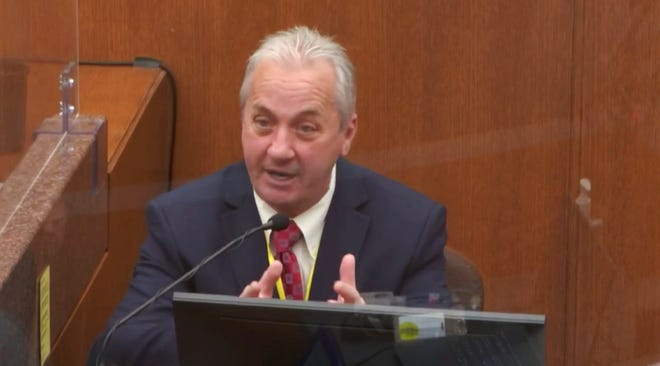

Richard Zimmerman, Minneapolis police veteran, testifies on use-of-force training

Lt. Richard Zimmerman, the Minneapolis Police Department's most senior officer in years served, testified Friday about the training officers receive. He said he’d been trained on having suspects in the prone position, meaning face down, since 1985. He has never been trained to kneel on the neck of a suspect who is prone – as Floyd was while Chauvin subdued him from above.

"That would be the top level of force," said Zimmerman, who also characterized it as potentially lethal danger.

"Once a person is in handcuffed, you need to get them out of the prone position as soon as possible because it restricts their breathing," said Zimmerman. "If you're laying on your chest, that's constricting them (breathing muscles) even more."

He noted that Minneapolis police officers are trained to abide by their department’s use of force continuum, which involves constantly revaluating and adjusting the level of force used on a person, depending on the threat that’s posed. After a person is in handcuffs, "the threat level goes down all the way," Zimmerman said.

Police are first responders, which means they can perform cardio-pulmonary resuscitation, and attempt to revive someone who’s not breathing. Minneapolis officers are trained on it every other year or so, he said. There is "absolutely" an obligation to provide medical intervention as soon as necessary to an injured suspect before an ambulance arrives with paramedics, Zimmerman said.

Based on his review of police body camera videos of the struggle and subduing of Floyd, Zimmerman said Chauvin’s knee on Floyd’s neck was “totally unnecessary."

"I saw no reason why the officers felt they were in danger, if that’s what they felt, and that’s what they would have to feel to be able to use that kind of force," he testified.

The top-level restraint should have been stopped while Floyd was prone and no longer resisting, he said.

During cross-examination, Eric Nelson, Chauvin’s lead defense attorney, tried to make Zimmerman appear out of touch with the dangers on Minneapolis streets and how police training has evolved since he last patrolled in 1993. Zimmerman acknowledged that his past few years of experience with force had been largely through police academy training sessions, not street patrol duty.

Nelson drew Zimmerman’s agreement that when a police officer is involved in a fight for life, "you are allowed to use whatever force is necessary." Zimmerman also acknowledged that a handcuffed person could still pose a threat to officers.

During the prosecution's re-questioning of Zimmerman, government lawyer Matthew Frank asked whether police training about potential dangers for a suspect held in the prone position had been adjusted over the years.

“That hasn’t changed,” said Zimmerman.

Citing his review of the police body camera videos, Zimmerman added that he did not see Floyd trying to kick Chauvin and other officers as he was held down.

Frank asked whether the bystanders watching the police struggle with Floyd posed an "uncontrollable threat" to the officers. Zimmerman said they did not.

"It doesn't matter – the crowd – as long as they're not attacking you," he said. "The crowd shouldn't have an effect on your actions."

Jon Edwards, Minneapolis police sergeant who responded to Cup Foods, testifies

Prosecutor Steve Schleicher questioned Jon Edwards, a Minneapolis Police Department sergeant currently on leave, as the first witness Friday.

Edwards told the court that he received a phone call from Sgt. David Pleoger, who said he was "at the hospital and he was with a male who may or may not live." So Edwards went to 38th and Chicago to secure the scene and start canvassing for witnesses, arriving about 9:35 p.m., roughly an hour after Floyd's initial arrest.

At this time, Edwards did not have a good grasp about the events that preceded Floyd's arrest, but upon responding, he briefly spoke with officers J. Alexander Keung and Thomas Lane and was the senior officer on the scene. Edwards ordered officers to put up crime tape surrounding the area where the confrontation between Floyd, Chauvin and the other officers took place. They also began canvassing for witnesses.

He secured the police squad and Floyd's car, which were later towed from the scene by Criminal Bureau of Apprehension, or the BCA, which took over the scene upon arrival.

Edwards didn't learn that the interaction with Floyd was a critical incident or that Chauvin was involved until later that night. Based on what learned from Keung and Lane, he told other officers to canvass the area, go door-to-door to look for witnesses and obtain a synopsis of what they may have seen.

Edwards, who spoke to a witness – a man named Charles who refused to speak about what he had seen – also spoke with the manager of Cup Foods. The manager said he didn't witness anything. Edwards learned later that Floyd had died and homicide investigators arrived on scene.

Keung and Lane went with other officers to the interview room at City Hall.

David Pleoger, former police supervisor: Officers 'could have ended' restraint of George Floyd

Thursday ended with David Pleoger, a recently retired Minneapolis police officer who was responsible for reviewing officers' use of force, who testified for nearly an hour Thursday afternoon.

After receiving a call from 911 dispatcher Jena Scurry — who testified Monday and said she didn't mean to be a "snitch," but that she had seen what happened to Floyd —Pleoger said he called Chauvin on his cellphone.

Much of the conversation was not recorded because Chauvin turned off his body camera, as allowed per policy. Pleoger said Chauvin told him restraint was used, Floyd suffered a medical emergency and they had called an ambulance. Pleoger told the court he didn’t think Chauvin told him that it was him who had held Floyd down or that he had placed a knee on Floyd’s neck.

“Would you agree that a person may be restrained only to the degree necessary to keep them under control,” Schleicher asked.

"Yes and no more restraint,” Pleoger said.

Schleicher also asked when the restraint of Floyd should have ended.

Pleoger replied, "When Mr. Floyd was no longer offering up any resistance to the officers, they could have ended their restraint."

Paramedic Derek Smith told partner 'I think he's dead'

Derek Smith, a paramedic with Hennepin County EMS, said he noticed that Floyd wasn't moving, was handcuffed and was being given no medical attention when he responded to the scene. He checked for a pulse and found none. He said Floyd's pupils were large and dilated.

"In lay terms, I thought he was dead. I told my partner, I think he's dead, and I want to move this out of here," he said.

Smith checked for a pulse again, found none and took off Floyd's handcuffs with his handcuff keys before removing him from the scene.

He told the officer riding in the ambulance to start compressions and he checked for pulse again. Smith said he was working the cardiac arrest "essentially alone," so he called for backup.

Smith administered a shock to Floyd and said he saw some pulseless electrical activity on the way to the hospital during a periodic check-in. Smith referred to Floyd as "deceased" when he was dropped off at the hospital.

As for why an officer rode with Smith to the hospital and he ordered that officer to do chest compressions, he told defense attorney Eric Nelson: "Any lay person can do chest compressions," he said.

Earlier Thursday, Smith's partner, Seth Bravinder, also took the the witness stand.

The Backstory:Derek Chauvin trial, repeated showing of George Floyd video, traumatizes witnesses, community — and journalists

George Floyd's girlfriend Courteney Ross gives jurors first glimpse of his personal life

George Floyd's girlfriend broke down in tears on the witness stand Thursday as she gave jurors an intimate glimpse at the "mama's boy," amateur athlete, restaurant lover and struggling drug user whose death prompted nationwide protests against police use of force last summer.

Courteney Ross said she had a relationship with Floyd for about three years after they met in Minneapolis in August 2017.

Floyd was usually very active, Ross said, and worked out every day. He often lifted weights. "Floyd loved playing sports with anyone who wanted to, including neighborhood kids. He's that person who'd just run to the store," she said.

He never complained about shortness of breath, she said.

Ross acknowledged that drug use was part of their relationship. The couple sometimes split up for a period but always got back together, she said.

"Floyd and I both suffered from opiate addiction," she said. "We both suffered from chronic pain. Mine was in my neck. His was in his back. We both had prescriptions. After prescriptions were filled, we got addicted, and we both tried, very hard, to break the addictions, many times." Read more.